HIKING HAPPENINGS - January 2026 |

|

| Take Me to the River: Hiking the Multi-Use Colorado Riverway Bike Trailby Kathy Grossman by Kathy Grossman |

|

|

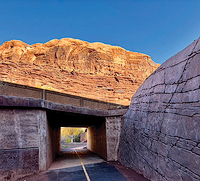

The riverway trail continues into the canyon, squeezed between the road and the river. I spotted Updraft Arch near the top of the cliff on the south side of the highway. On my left at about Mile 1 of the riverway, I noticed a patch of dark green, rough cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium), where I turned south into the lovely Memory Grove with a bench and several memorial plaques affixed to some rock faces. A dirt path then leads south up to a large parking area with picnic tables, restroom, and interpretive signs. As I huffed up the hill, a friendly yellow head popped into view. It was Larry the Collared Lizard! Larry is a 20-foot-long yellow-and-turquoise sculpture with sparkly, green glass eyes. Just installed in November, this artwork is also a bench that faces the river. Local artist Serena Supplee created Larry in cooperation with the Canyonlands Natural History Association and the Bureau of Land Management Moab Field Office. This chilly morning, Larry was covered in a frosty scrim, barring any contemplative sitting for me, so I kept walking. I passed Goose Island Campground (around Mile 2), where hardy souls were making coffee and serving breakfast to children and dogs. The riverway ends with a whimper about a half-mile beyond the campground. Another quarter mile away, the Grandstaff Canyon Trailhead appears across 128 on the right/south in a gap in the cliffs. A riverway extension is planned for next year, ending opposite this trailhead. Open throughout the year, this path is not maintained during the winter, so be cautious with snow and ice (trekking poles might help), especially in any shaded sections.

Kathy Grossman is an artist, nature journalist, hiker, and writer who’s lived in Moab since 2011.

Her scratchboard rendering of an eastern collared lizard hangs in our library. Kathy Grossman is an artist, nature journalist, hiker, and writer who’s lived in Moab since 2011.

Her scratchboard rendering of an eastern collared lizard hangs in our library. |

|

© 2002-2026 Copyright Moab Happenings. All rights reserved.

Reproduction of information contained in this site is expressly prohibited without the written permission of the publisher.

The Colorado River was a sheet of glass this calm, winter morning, perfectly mirroring the sandstone cliffs and vegetation on the north riverbank. I was exploring the riverway trail that runs between Highway 128 (the River Road) and the Colorado for 2.5 miles. Though labeled a bike trail, this paved pathway is for multiple users. I saw bike-riders, but also joggers, runners, and walkers with some very good dogs on leash. A family of 12, ranging from perhaps 7 to 60, each on individual bikes, came flying past, each one calling out greetings. I stayed alert for bells and calls of “on your left!” as I followed my lane, honoring the center line.

The Colorado River was a sheet of glass this calm, winter morning, perfectly mirroring the sandstone cliffs and vegetation on the north riverbank. I was exploring the riverway trail that runs between Highway 128 (the River Road) and the Colorado for 2.5 miles. Though labeled a bike trail, this paved pathway is for multiple users. I saw bike-riders, but also joggers, runners, and walkers with some very good dogs on leash. A family of 12, ranging from perhaps 7 to 60, each on individual bikes, came flying past, each one calling out greetings. I stayed alert for bells and calls of “on your left!” as I followed my lane, honoring the center line.