SUSTAINABILITY HAPPENINGS September 2020 |

||||

| Moab Community Funds Solar Dehydrator Project by Kate Weigel & Roslynn Brain McCann |

||||

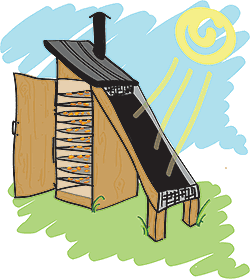

The USU Permaculture Initiative, Bee Inspired Gardens, Resiliency Hub, the Local Food Task Force for Grand County, and Youth Garden project have teamed up to build a solar dehydrator for community use. The project raised over $1,000 in August along with a generous in-kind donation from both Walker True Value Hardware and USU Extension Sustainability. It will be built and located on-site at Youth Garden Project (530 S 400 E, Moab, UT) and will be available for use in early September. The cost of renting the solar dehydrator will be $10 per day. Sliding scale rental fees will also be available to make this resource accessible to all who may benefit. In addition, the community kitchen at YGP will be available for

The dehydrator uses the power of the sun to move air currents through horizontal food-safe screens in a small shed-like structure. The downdraft style of the dehydrator means that the sun heats air in a clear chute on the exterior of the dehydrator. This warm air then travels upward into the top of the fruit-drying chamber. As the air cools inside the chamber, it falls to the bottom where it is sucked out through a venting chimney to the roof. This constant flow of air and heat sucks the moisture out of all kinds of different vegetables and fruits. There will be approximately twelve large screens inside the drying chamber, allowing community members to preserve many pounds of produce at one time. Not only is it much bigger than a typical dehydrator allowing for significantly larger batches, it also uses no electricity. Dried fruit is an excellent source of nutrients, containing much of the same vitamins, minerals and fiber as fresh fruit in a long-lasting, smaller package. Preserving food this way helps to spread out the bounty of the summer months so delicious local harvests can be enjoyed all year long. This resource will be a permanent fixture at YGP, where it will preserve healthy food for the community for many years to come. If you would like to schedule a time to use the dehydrator for your own harvest, contact Emily Roberson at community@youthgardenproject.org. Additionally, if you have more vegetables or fruit than you can use on your property or business, contact the Moab Gleaners via their Facebook page. They can send volunteers to collect the extra harvest and will donate a portion of it to one of the area food banks. |

||||

| Expanding the Green Waste Lifecycle by Jessica Thacker, Program Manager (Solid Waste Special Service District #1) |

||||

| “Often when you think you’re at the end of something, you’re at the beginning of something else.” – Fred Rogers Mr. Rogers, the iconic friendly neighborhood personality, always ended his shows with a lesson learned that could be applied to every facet of human living. The above quote can be applied to the concept of waste management, recycling, and sustainable ‘closed-loop’ environmental cycles. However, the world of ‘being green’ and how to achieve it can easily overwhelm anyone. Let us focus on one relatively unknown but unsurprising method: green waste reclamation.

There are a wide range of methods and benefits associated with green waste reclamation: composting, green waste recycling and reuse, and alternative material supply. The first question we ask ourselves is why is reducing green waste so important? There is a common misconception that green waste is at the end of its lifecycle with no foreseeable beneficial reuse. Fortunately, there are a variety of beneficial recycling and reuse opportunities for this organic material. Composting, whether on a residential or commercial scale, is a science of its own. While composting activities need to be tailored to the specific environment it is located in, it is a relatively simple activity that provides a variety of benefits such as a reduced carbon footprint, reduced need for artificial and chemical fertilizer, water conservation through soil moisture retention, and enrichment of local crops. Composting can be accomplished through green waste, food waste, or a combination of both, mainly through the correct ratio of carbon, nitrogen, and moisture content. If backyard (or indoor) composting is not feasible at your home, composting through local waste management entities or commercial organizations and businesses is another option. One such organization is the Youth Garden Project, 530 South 400 East St. They employ the use of composting in their community gardens, encourage locals to tour their composting sites, and provide educational resources online. Green waste recycling such as mulching of yard waste is another beneficial reuse strategy for old, unwanted branches, logs, brush, and other organics currently sitting in your backyard. By properly sorting (removing rocks, clumps of soil, and other inorganic debris) and delivering green waste materials to acceptable locations, such as the Moab Landfill (fees apply), these materials can be used to create quality mulch. In 2020, the Solid Waste District reclaimed more than 8,000 cubic yards of green waste at the Moab Landfill that is currently for sale as unscreened mulch. Quality mulch made from reclaimed green waste can provide a variety of benefits–it can increase soil moisture retention rates, moderate soil temperatures, limit plant disease, and prevent soil erosion. Mulching discarded green waste can also prolong usable airspace at landfills for non-reclaimable material, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and leachate production in particular environments, assist local fire departments in removing potential wildfire fuels during the hot and dry months of the year, and be used as a composting feedstock. Another inspiring and surprisingly creative method of green waste reclamation is using these materials as alternative feedstocks in agriculture, permaculture, or even architecture. Moab is home to one such example, TerraSophia, a Moab-based landscape contracting firm that provides permaculture design-build through a holistic approach. For example, old branches can be repurposed to weave garden trellis or lightweight fencing and retaining walls. By creatively altering the original purpose of the organic material, the life cycle is expanded in an unusual way and transforms these typically unwanted, discarded materials to a functional, beneficial reuse product in a sustainable and environmentally compatible manner. Green waste has a lifespan that can be circular, always beginning when the end is assumed. By taking material previously thought to be unusable and repurposing it, we can be a friendly neighbor to our local community and environment. |

||||

| Reconciling with a

Drier Desert By Kristina Young This piece first appeared in The Dust magazine |

||||

I am not an optimist. My coping skills for the state of the world are employing geologic time. When trending towards despair I consider that life will survive for eons to come, it will just be different from the spiny, desiccated desert life I know and love. I told this once to an Indian Rice Grass, a species native to my home on the Colorado Plateau who had the misfortune of evolving a method of photosynthesis not predicted to withstand a warmer world. It seemed less concerned than I was. That is the price, I suppose, of knowing and loving a place: grave concern for its future and well-being. My job as a scientists involves looking at data. The data I am looking at confirms we are not going back to the climatic or hydrologic regimes we knew. Instead, we are likely facing aridification: a process of increasing dryness where air and soil contain less and less water over time. Aridification is different from the droughts we know. Droughts are temporary. Aridification is when a place becomes consistently drier. Water increasingly scarce for living things. I tried to picture the red Moab sand drier than it already is. The hair-dryer like wind in the summer, even drier. In the distance I heard a prickly pear cactus sob. What often accompanies aridification is desertification, a process where a dry region is degraded through interactions between climate and land use, becoming less biologically and economically productive through time. In Southern Utah desertification looks like increased levels of soil erosion, loss of grasses, and mounded shrubs with bare areas of eroding soil in between. Dust as our constant companion. Aridification and desertification are of the same ilk. These processes can transform dry places until they are unrecognizable. The patch of desert around Moab I know and love could degrade before my eyes under the force of these combined processes.  But I don’t want this desert to degrade. The fourwing salt bush would never forgive me. Luckily there are research-based solutions to making the deserts of Southern Utah more resistant to the coming dryness. Currently there are multiple land use pressures on these drying places that disturb vegetation and soil, such as recreation, grazing, development, and resource extraction. Each activity exerts a pressure which, when combined with aridification, can lead to desertification and run-away ecological change. To reduce the number of pressures, policy and management can use data to act with foresight about the ways we use the desert of Southern Utah, strategically reducing the extent or duration of each land use. Surely we can use the large amount of science available to equip land managers with solutions that maintain economies, traditions, and cultures while reducing undue pressure on these fragile, living places. If not, I hope you like dust. Maybe I am an optimist, I said out loud to a buckhorn cholla on a hot desert day. The cholla stood there, thirsty, and never answered. |