HIKING HAPPENINGS December 2011

Aztec Butte – Clues To An Ancient Culture

article and photos by Marcy Hafner

Island In The Sky, with an average elevation of 6100 feet, is the highest portion of Canyonlands National Park. Situated like a desert island, this sheer-walled plateau is surrounded by a far-reaching, isolated landscape, which drops precipitously down to the surging waters of the Colorado and Green Rivers. On a clear day, a person can cast his vision almost 100 miles across a tangled web of canyons, mesas, buttes, fins and spires – a wondrous horizon-to-horizon view climaxed by three distinct mountain ranges – the La Sals to the east, the Abajos to the south and the Henry Mountains to the west. Island In The Sky, with an average elevation of 6100 feet, is the highest portion of Canyonlands National Park. Situated like a desert island, this sheer-walled plateau is surrounded by a far-reaching, isolated landscape, which drops precipitously down to the surging waters of the Colorado and Green Rivers. On a clear day, a person can cast his vision almost 100 miles across a tangled web of canyons, mesas, buttes, fins and spires – a wondrous horizon-to-horizon view climaxed by three distinct mountain ranges – the La Sals to the east, the Abajos to the south and the Henry Mountains to the west.

Somewhere in time - many centuries ago - groups of ancestral Puebloans (formerly known as Anasazi) lived within the boundaries of the park. Pressured by the growing populations around Mesa Verde, they had migrated to Utah’s Canyonlands searching for more suitable land to grow their crops of corn, squash and beans. By 1200 A.D., these early farmers had settled in scattered areas throughout the park wherever water was abundant including along the Green River. They, however, still practiced the hunter-gatherer lifestyle and regularly climbed the steep 2,000 foot terrain to the Island In The Sky mesa for that purpose. During those travels, they also built granaries, and one of the best examples of those ancient structures is in the vicinity of Aztec Butte - a prominent landmark that is visible for a long distance. Somewhere in time - many centuries ago - groups of ancestral Puebloans (formerly known as Anasazi) lived within the boundaries of the park. Pressured by the growing populations around Mesa Verde, they had migrated to Utah’s Canyonlands searching for more suitable land to grow their crops of corn, squash and beans. By 1200 A.D., these early farmers had settled in scattered areas throughout the park wherever water was abundant including along the Green River. They, however, still practiced the hunter-gatherer lifestyle and regularly climbed the steep 2,000 foot terrain to the Island In The Sky mesa for that purpose. During those travels, they also built granaries, and one of the best examples of those ancient structures is in the vicinity of Aztec Butte - a prominent landmark that is visible for a long distance.

To get to Island In The Sky, drive ten miles north of Moab on Highway 191. At Highway 313, turn left and drive another 25 miles to the park’s entrance station. To get to Island In The Sky, drive ten miles north of Moab on Highway 191. At Highway 313, turn left and drive another 25 miles to the park’s entrance station.

On my last visit to the park, I stopped at the visitor center to make some inquiries about the granaries, and the ranger informed me that due to a rock slide, the trail up the steep slickrock to the top of Aztec Butte had been closed. A spur trail, however, to a small hill on the west side of Aztec Butte remained open to two easily accessible granaries, which remained in excellent condition. After that conversation, I drove approximately five more miles to a stop sign, where I turned right in the direction of Willow Flat Campground and Upheaval Dome. Parking for Aztec Butte isn’t far beyond that turn.

During the first part of this easy-going sandy trail, I am i mpressed with the healthy growth of blackbrush, pinyon pines, junipers, Mormon tea, sagebrush and Indian rice grass. The various buttes fascinate me – each one displaying its own trademark size and shape from a gentle cone to a sharp-edged slanted protrusion that abruptly shoots up from the ground. But the most dominant structure is the mystical image of Aztec Butte, as its dimensions imaginatively suggest an Aztec pyramid - a hefty chunk of pale white rock, which steeply angles upward from a light brown base to its flat-cropped top, where a small forest of pinyon pines and junipers thrive. mpressed with the healthy growth of blackbrush, pinyon pines, junipers, Mormon tea, sagebrush and Indian rice grass. The various buttes fascinate me – each one displaying its own trademark size and shape from a gentle cone to a sharp-edged slanted protrusion that abruptly shoots up from the ground. But the most dominant structure is the mystical image of Aztec Butte, as its dimensions imaginatively suggest an Aztec pyramid - a hefty chunk of pale white rock, which steeply angles upward from a light brown base to its flat-cropped top, where a small forest of pinyon pines and junipers thrive.

At the fork, a faded sign clearly indicates that the trail to Aztec Butte is closed, and I continue along the spur trail towards the lower butte. Soon piles of rock called cairns indicate the best way up the short gentle grade to the top. Then one small boost over the final ledge, and I’m standing on firm ground with an even more dynamic view of Aztec Butte. At the fork, a faded sign clearly indicates that the trail to Aztec Butte is closed, and I continue along the spur trail towards the lower butte. Soon piles of rock called cairns indicate the best way up the short gentle grade to the top. Then one small boost over the final ledge, and I’m standing on firm ground with an even more dynamic view of Aztec Butte.

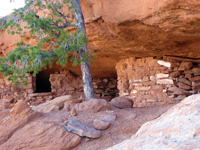

The trail now makes a loop along the perimeter of the mesa, and I travel the counterclockwise direction. Gingerly dropping down just below the rim on the west side, I discover the granaries tucked away inside a small alcove. On this rocky ledge a pinyon pine has defied the odds – despite the lack of soil, it has somehow managed to mature into a tall tree. These well-preserved dwellings, which were constructed long before this pine was even born, have withstood the test of time and the elements. The three foot high rock and mortar walls are still intact, and each granary has a rectangular hole for access with a ledge - one is even framed with pieces of wood.

This well-protected alcove must have been a pleasant place for these resourceful people to finally stop after a long haul up the steep canyon - a huge relief to drop their heavy load of food! And while they rested they could look out on this expansive view of The Henry Mountains, the Bookcliffs and the staggering vastness of the Canyonlands scenery. This well-protected alcove must have been a pleasant place for these resourceful people to finally stop after a long haul up the steep canyon - a huge relief to drop their heavy load of food! And while they rested they could look out on this expansive view of The Henry Mountains, the Bookcliffs and the staggering vastness of the Canyonlands scenery.

As I stretch out on the front porch, I ponder the arduous back-breaking work they must have endured to get their food stocks up here – to build these granaries so far away from their fields, the reasons must have been compelling. The explanations for this strange activity are varied - maybe they wanted a measure of security – if something happened to their food supply along the river, they still had this cache on the mesa. Possibly, they didn’t trust their marauding neighbors or enemies. To me, however, the most plausible theory is they built these granaries to be used during their hunting-gathering trips on the mesa. As I stretch out on the front porch, I ponder the arduous back-breaking work they must have endured to get their food stocks up here – to build these granaries so far away from their fields, the reasons must have been compelling. The explanations for this strange activity are varied - maybe they wanted a measure of security – if something happened to their food supply along the river, they still had this cache on the mesa. Possibly, they didn’t trust their marauding neighbors or enemies. To me, however, the most plausible theory is they built these granaries to be used during their hunting-gathering trips on the mesa.

Over the years, changing weather patterns to a dryer climate made farming more difficult. The depletion of the clan’s natural resources added another stress factor to their sustainability. Eventually they had no other choice but to move on to greener pastures, and various groups gradually drifted away. For a long time, the common belief was that they just mysteriously disappeared, but strong scientific evidence now suggests they probably joined the Hopi and Zuni co Over the years, changing weather patterns to a dryer climate made farming more difficult. The depletion of the clan’s natural resources added another stress factor to their sustainability. Eventually they had no other choice but to move on to greener pastures, and various groups gradually drifted away. For a long time, the common belief was that they just mysteriously disappeared, but strong scientific evidence now suggests they probably joined the Hopi and Zuni co mmunities in New Mexico and Arizona and Pueblo villages along the Rio Grande. mmunities in New Mexico and Arizona and Pueblo villages along the Rio Grande.

By 1300 these ancient people had completely vacated their homeland leaving behind only traces of their past. Archeologists have unearthed a tremendous amount of information about the lifestyle of this tribe of Native Americans, but so much about their passage remains a haunting conundrum, and those unanswered questions remain buried in the shifting sands of the desert.

|

Biological Soil Crust (aka)

Cryptos (krip’ tose):

The surface of

Moab’s desert is held

together by a thin skin of living organisms known as cryptobiotic

soil or cryptos. It has a lumpy black appearance, is very

fragile, and takes decades to heal when it has been damaged.

This soil is a critical part of the survival of the desert.

The cryptobiotic organisms help to stabilize the soil, hold

moisture, and provide protection for germination of the seeds

of other plants. Without it the dry areas of the west would

be much different. Although some disturbance is normal and

helps the soil to capture moisture, excessive disturbance

by hooves, bicycle tires and hiking boots has been shown

to destroy the cryptobiotic organisms and their contribution

to the soil. When you walk around Moab avoid crushing the

cryptos. Stay on trails, walk in washes, hop from stone to

stone. Whatever it takes, don’t crunch the cryptos

unless you absolutely have to! |

Cryptobiotic soil garden

|

|

|