I

knew I would love this hike. Still, Negro Bill Canyon and the

Morning Glory Bridge far surpassed my expectations in every

way. I

knew I would love this hike. Still, Negro Bill Canyon and the

Morning Glory Bridge far surpassed my expectations in every

way.

The Bureau of Land Management trail (which have become my personal favorites

for their convenience, relative ruggedness and dog-and-kid friendliness)

is just over two miles from Highway 191 in Moab on State Highway 128,

also known as the River Road. A large pullout on the right side of the

road is usually full of cars, testimony to the trail’s popularity,

yet I encountered few people one late afternoon in mid-September as I

traversed the creek bed, prickly pear forests and boulders to the end

of the trail.

Negro Bill Canyon is named for one of Moab’s first non-native settlers,

William Granstaff, who came to the valley in 1877. It’s easy to

imagine why William chose this canyon; a perennial, clear-running stream

meanders and is home to beaver, who build and rebuild pools inviting

to the meekest swimmers or waders. The pools are surrounded by sand;

perfect for picnicking, and juniper berries, the fruit of prickly pear

and a variety of sweet-smelling, delicate and vividly colorful flowers

grace the path to this day. Fish spawn and swim at your feet as you cross

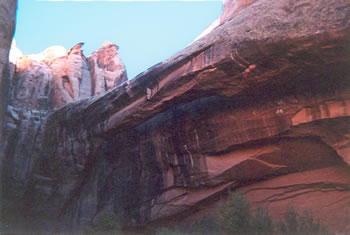

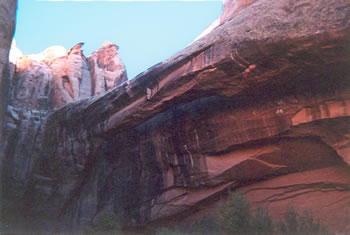

the creek several times on the way to Morning Glory Bridge, a “natural

bridge” boasting recognition as the sixth largest rock span – 243

feet - in the United States.

The

elevation gain on this hike is 330 feet, most of it gradual with

sharper inclines just before what locals call “the first

side canyon,” and again just before the end of the trail.

It used to be hikers could get lost or confused on their way

to Morning Glory Arch, and it could still happen. But suspect

junctures are marked with trail signs, and cairns are more prevalent

as the landscape widens and dirt and sand paths turn to rock

from rim to rim. Most of the trail is narrow, which makes it

a good hike with young children and pets because they can’t

run off. It is also shaded much of the way, and with the pools

I found myself wondering ‘Why be hot in Moab?’ This

place is cool. The

elevation gain on this hike is 330 feet, most of it gradual with

sharper inclines just before what locals call “the first

side canyon,” and again just before the end of the trail.

It used to be hikers could get lost or confused on their way

to Morning Glory Arch, and it could still happen. But suspect

junctures are marked with trail signs, and cairns are more prevalent

as the landscape widens and dirt and sand paths turn to rock

from rim to rim. Most of the trail is narrow, which makes it

a good hike with young children and pets because they can’t

run off. It is also shaded much of the way, and with the pools

I found myself wondering ‘Why be hot in Moab?’ This

place is cool.

In fact, in the winter months

is when Negro Bill Canyon first attracted my attention because

of the beautiful, ornate icicles visible from the road. I

always thought it would be a good winter hike, but was warned

off because it does get slippery with ice on the trail a

couple of months out of the year. But until December, the

trail offers a colorful view of fauna native to this area

in abundance unlike Moab’s common landscape. It is

a Wilderness Study Area, and therefore protected from trampling

as it is being considered for eventual and total Wilderness

status.

Hikers may want to beware the also colorful poison ivy along this trail.

Because the trail is maintained, the ivy is relatively easy to avoid.

I took one wrong turn and in trying to avoid the ivy found myself full

of prickly pear – one thorn and hundreds of the cactus’s

small weapons, which I likened to a spear and hundreds of knives. I packed

them with mud and soaked in the stream and got them all out within 12

hours unscathed; prior to the literal “falling out,” I was

bragging to myself that the trail offered just enough “scramble” for

me to feel like a kid and not get hurt. I stand by that. It is a scramble

in places, and a fun one. Walking the trail felt like dancing in some

ways, and the stream offered the music.

At

the Arch and Bridge, the sound intensifies. Powerful, rushing

water sounds with only a still, shallow marshy pool in sight.

I venture closer to the Bridge and see a trickle coming from

a rock formation a hundred feet above me. I sit at the foot of

this formation – the sixth largest in the U.S. and wonder,

is it another arch in the making? At

the Arch and Bridge, the sound intensifies. Powerful, rushing

water sounds with only a still, shallow marshy pool in sight.

I venture closer to the Bridge and see a trickle coming from

a rock formation a hundred feet above me. I sit at the foot of

this formation – the sixth largest in the U.S. and wonder,

is it another arch in the making?

It feels like it could happen any second, hence my apprehension, yet

it will probably take millennium. It makes me dizzy, and I run, like

a kid, back to the trailhead, hoping I catch my friends in time for dinner

in town. I did.

The trail is two miles one way, an easy two-to-three-hour hike. Bring

lots of water, your kid and/or dog, and food. Stay a while. The music

is good.

Bikes and vehicles are prohibited on the trail.

Cryptos (krip’ tose):

The surface of Moab’s desert is held together

by a thin skin of living organisms known as cryptobiotic

soil or cryptos. It has a lumpy black appearance,

is very fragile, and takes decades to heal when

it has been damaged. This soil is a critical part

of the survival of the desert. The cryptobiotic

organisms help to stabilize the soil, hold moisture,

and provide protection for germination of the seeds

of other plants.

Without

it the dry areas of the west would be much different.

Although some disturbance is normal and helps

the soil to capture moisture, excessive disturbance

by hooves, bicycle tires and hiking boots has

been shown to destroy the cryptobiotic organisms

and their contribution to the soil. When you

walk around Moab avoid crushing the cryptos.

Stay on trails, walk in washes, hop from stone

to stone.

Whatever

it takes, don’t crunch the cryptos unless

you absolutely have to! |

|

I

knew I would love this hike. Still, Negro Bill Canyon and the

Morning Glory Bridge far surpassed my expectations in every

way.

I

knew I would love this hike. Still, Negro Bill Canyon and the

Morning Glory Bridge far surpassed my expectations in every

way. The

elevation gain on this hike is 330 feet, most of it gradual with

sharper inclines just before what locals call “the first

side canyon,” and again just before the end of the trail.

It used to be hikers could get lost or confused on their way

to Morning Glory Arch, and it could still happen. But suspect

junctures are marked with trail signs, and cairns are more prevalent

as the landscape widens and dirt and sand paths turn to rock

from rim to rim. Most of the trail is narrow, which makes it

a good hike with young children and pets because they can’t

run off. It is also shaded much of the way, and with the pools

I found myself wondering ‘Why be hot in Moab?’ This

place is cool.

The

elevation gain on this hike is 330 feet, most of it gradual with

sharper inclines just before what locals call “the first

side canyon,” and again just before the end of the trail.

It used to be hikers could get lost or confused on their way

to Morning Glory Arch, and it could still happen. But suspect

junctures are marked with trail signs, and cairns are more prevalent

as the landscape widens and dirt and sand paths turn to rock

from rim to rim. Most of the trail is narrow, which makes it

a good hike with young children and pets because they can’t

run off. It is also shaded much of the way, and with the pools

I found myself wondering ‘Why be hot in Moab?’ This

place is cool. At

the Arch and Bridge, the sound intensifies. Powerful, rushing

water sounds with only a still, shallow marshy pool in sight.

I venture closer to the Bridge and see a trickle coming from

a rock formation a hundred feet above me. I sit at the foot of

this formation – the sixth largest in the U.S. and wonder,

is it another arch in the making?

At

the Arch and Bridge, the sound intensifies. Powerful, rushing

water sounds with only a still, shallow marshy pool in sight.

I venture closer to the Bridge and see a trickle coming from

a rock formation a hundred feet above me. I sit at the foot of

this formation – the sixth largest in the U.S. and wonder,

is it another arch in the making?