A painting is a reflection

of the artist much like a child reflects a parent. The artist,

consciously and otherwise, imparts portions of his experiences

and philosophies into a work of art.

This connection between creator and creation

makes studying the body of work of an artist particularly

fascinating since it’s a way of delving into the mind

of the person. For example, before Picasso painted his signature

cubist faces, he explored a “Blue Period,” in

which he realistically depicted figures in varying hues of

blue. The transition from focusing on a color that casts

a depressing tone to each canvas to what eventually became

a revolutionary interest in strong linear and colorful abstract

paintings is intriguing since it reflects the evolution of

a creative, perceptive mind.

Much like Picasso’s later portraits which depict fractured

facets of the face from one point of perception, Alex Burbidge’s

portfolio includes such varying styles, revealing many sides

to an inquisitive, insightful spirit.

Not only is Burbidge prolific in the amount of work he has

created, but he has also explored so many divergent ideas

and ways to depict them through art that he eludes being

pinned down by a label.

To begin with, I was under the impression that he was a sculptor

since my first introduction to his work was at the Moab Abstracts

exhibit in February, which featured modern art by six local

residents. Burbidge’s contribution to the show was

sculptures made of wire.

Having majored in sculpture at the University of Utah, Burbidge

has created other three-dimensional works, including carved

figurines and masks, a subject that fascinates him.

The hallway of his home is decorated with an impressive collection

of masks. Some are ones he created himself and others have

been acquired as gifts or from his own travels. The materials

they are made of include wood, paper mache, feathers and

beads. The ones designed by Burbidge are designed to be worn,

a manifestation of his belief that people wear figurative

masks all the time. This idea surfaces in much of his artwork.

Nowadays, painting is the primary medium through which he

explores this philosophy.

Although my encounters with Burbidge have been few, he strikes

me as a soft-spoken man, keeping his tone level and low,

hands anchored under his crossed arms. Juxtaposing this impression

of the artist against his vibrant work echoing of social

commentary reveals how he uses his paintings as a forum for

eloquent visual discourse and social commentary.

Burbidge likes to explore diverse styles, moving from one

series of paintings to another. Perusing his portfolio is

like reading all the novels of one author. Although his style

evolves, becoming more sophisticated in his later works,

the central themes remain the same.

Clearly, he is an observer of human nature. One of his earlier

series of paintings that he began in 2002 is made up of canvases

that trick the eye into believing they are a collage of images.

In “Human Ideology: One Step Forward, Two Steps Backwards”,

he depicts an arrangement of what appears to be disconnected

images, ranging from an orangutang hanging out of a tropical

forest to a black-and-white image of a well-dressed couple

embracing. The latter image is sandwiched between a picture

of swimming chromosomes above it and a burning hillside below

it, reflecting the biological underbelly of the romantic

scene.

Seven faces displaying varying expressions run along the

top of the painting, representing the range of emotions art

can extract from the viewer. Those faces appear to be an

invitation or a warning to the viewer that these images are

meant to evoke an array of feelings and thoughts.

Burbidge effectively uses different tones to distinguish

one image from another. The warm colors of the African tribal

woman contrast to the cooler blues of the urban man wearing

a top hat. The most arresting aspect of the painting is the

pair of gray hands at the bottom of the canvas that seem

to rest in a supplicating pose over the collage. In the pose,

Burbidge has caught the feeling of despair and wonder since

it is not clear whether the hands are raised in anguish or

are being held up in order to admire them and what they can

accomplish.

The other paintings in this series display the same raw emotion,

laying Burbidge’s ideas and questions out directly

on the table. Another similar painting includes images of

a semi-dressed woman kneading dough, a wolf howling and a

soldier loading a gun. The center of this painting brandishes

a caption reading, “Human Idealogy: Eat it, Kill it

or F**k It.”

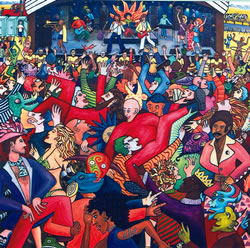

In his next series, entitled “Spinning on a Tilted

Axis,” Burbidge continues to address the human condition

with a forthright voice. Using bold colors, where red and

royal blue dominate, he creates vibrant compositions that

demand attention.

His canvases are populated by a multitude of interlaced figures,

creating movement and chaos in the composition. This series

seems less didactic than the previous, and appears to be

more of an exploration of the relationships between people,

cultures and religion.

A consistent figure in all of these paintings is “Mama

Gaya,” who is identifiable by her multi-colored gown,

symbolic of the tapestry of life and all its tones and shapes.

Her face wears a serene expression of calm or enlightenment.

In “When Your Insides Are Out and Outsides Are In,” she

is depicted with her eyes closed in what appears a meditative

pose while holding up horned masks in her crossed arms. The

masks partially cover the faces of two men crouching behind

her, each with an opposing expression to the one worn by

the mask in front of his face. It is not clear if Mama Gaya

is helping to take off the masks or switching them from one

man to the other.

This idea of people hiding behind masks surfaces clearly

throughout this series of paintings, evidenced in a depiction

of the crucifixion where every figure below Christ is wearing

a full-facial mask.

Religion, both in terms of philosophy and cultural identity,

seems to be a topic Burbidge does not tire of exploring,

and it plays a central role in his next series of paintings,

entitled “The Travels of Jesse and Buddy.” Playing

on the names of Jesus and Buddha, Burbidge uses these paintings

to explore how these central figures of major world religions

fit into quotidian life today by placing them in familiar

scenes, such as a rodeo, a volleyball tournament, a barbershop

and a mosh pit.

These paintings continue to use bold color and intentionally

flat dimensions, which imbue them with a cartoon-like quality,

a playful invitation to consider the more serious ideas the

painter is exploring through the composition. This series

clearly reflects how Burbidge has emerged from a didactic

phase into one of contemplation and dialogue.

The ideas that drive him remain the same. In fact, the “Mama

Gaya” figure makes cameo appearances throughout this

later series, appearing in the background of most of these

paintings. Burbidge explores how religions blend in a global

world, reflected in the number of ethnicities represented

by the people who populate these paintings. The cartoon-like

quality of this series belies the depth with which he considers

these complicated ideas.

His most recent series of paintings is taking him into the

world of abstracts. The bold colors and lines of his past

paintings are still present in these newest ones. Although

recognizable images appear in the current works, the overall

effect is non-representational. Burbidge begins with an idea

and overlays colors and marks until the canvas takes on an

appearance of its own. The original image remains, but the

viewer has to look for it.

In “Tree of Life-Study,” a painting Burbidge

created for his wife, Julia, the turquoise and red lines

pop out in the shape of a tree. Looking closely at the tree,

a man and woman facing each other appears in the trunk. Between

their torsos lie concentric hearts and between their legs

is the shape of a child. Other recognizable figures emerge

from the leaves, but the dominating image of the painting

is color and lines.

Along with these divergent series, Burbidge has continued

painting nature, in the form of floral still lifes, and most

currently, “pleine aire” scenes of the desert

landscapes. He works with oils, using a palette knife to

create a thick texture. Where he is willing to turn a critical

and contemplative eye on the human condition, he depicts

nature in its softest, most docile moments, capturing spring

vegetation along a river, autumn leaves and curvaceous sandstone.

Reviewing Burbidge’s portfolio is an introduction to

the artist because he imbues so much of his work with his

personal philosophies. His paintings, particularly those

which compose a series, act like masks. Behind each series

lies a part of the man who created them.

Like the Wizard of Oz, Burbidge prefers standing behind his

creations, as evidenced by the pen name “Alea” he

uses to sign his works. Also like the Wizard, he succeeds

in creating such vivid, fascinating and revealing paintings

that the viewer can easily forget to peek around and see

the man quietly pulling the strings in the background, an

interesting juxtaposition between a soft-spoken man and his

vociferous ideas.

|