|  About

10 years ago, Naya Raines woke with a start, sat upright,

and said out loud: “I think I need to weave.”

She had not consciously desired to weave or seriously considered

weaving before this sudden outburst. Shortly thereafter, she

took a Navajo weaving workshop on the reservation which she

lived. And although over the years she has appropriated new

methods, techniques and styles, she has continued to weave

with passion and a love for the art until this day. About

10 years ago, Naya Raines woke with a start, sat upright,

and said out loud: “I think I need to weave.”

She had not consciously desired to weave or seriously considered

weaving before this sudden outburst. Shortly thereafter, she

took a Navajo weaving workshop on the reservation which she

lived. And although over the years she has appropriated new

methods, techniques and styles, she has continued to weave

with passion and a love for the art until this day.

Weaving is virtually as old and as enduring as human civilization

itself. There is evidence that the Egyptians, 5000 years ago,

made special tapestries for the pharaohs in select colors

and patterns signifying their royal and spiritual heritage.

Ancient Greek pottery, from 540 BCE, portrays women weaving

cloth on large looms in the name of Athena, goddess of weaving

as well as war. The Navajo, or the Diné people, learned

weaving from Pueblo refugees in the late seventeenth century,

but quickly developed their own style and refinements to the

craft of weaving, allowing their weavings to express their

stories, histories and their culture.

Like

the Navajo, from which she learned to weave, Raines appreciates

weaving as a holistic process, combining mind, body, emotions

and spirit into the craft. The art of weaving express her

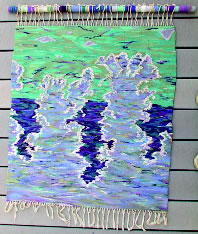

self, her story and her environment. For example, Raines began

working on “ Ciaramallow’s Dream” while

she lived at the ocean. The colors and the forms started out

as ocean waves: the blues and purples smeared together like

the many colors of the ocean and the interplay of light. Wave

forms appeared on the tapestry in the form of white, bubbling

crests. In mid-tapestry, Raines moved to the Southwest, where

she continued the tapestry. A transformation happened, however,

and her Like

the Navajo, from which she learned to weave, Raines appreciates

weaving as a holistic process, combining mind, body, emotions

and spirit into the craft. The art of weaving express her

self, her story and her environment. For example, Raines began

working on “ Ciaramallow’s Dream” while

she lived at the ocean. The colors and the forms started out

as ocean waves: the blues and purples smeared together like

the many colors of the ocean and the interplay of light. Wave

forms appeared on the tapestry in the form of white, bubbling

crests. In mid-tapestry, Raines moved to the Southwest, where

she continued the tapestry. A transformation happened, however,

and her  waves

began to morph into dancing figures like Kachina and the tapestry

took on a whole new appearance, reflecting Raines’ internal

and external transition to a new environment. The art and

process of weaving gives Raines a lot of pleasure. The actual

weaving is simple to learn and therefore the process is calm,

rhythmic and meditative. Raines added that in the process

of weaving and creating she feels most connected to God or

to a Higher Order. And therefore, weaving gives her satisfaction

and spiritual fulfillment, as well as a creative outlet. waves

began to morph into dancing figures like Kachina and the tapestry

took on a whole new appearance, reflecting Raines’ internal

and external transition to a new environment. The art and

process of weaving gives Raines a lot of pleasure. The actual

weaving is simple to learn and therefore the process is calm,

rhythmic and meditative. Raines added that in the process

of weaving and creating she feels most connected to God or

to a Higher Order. And therefore, weaving gives her satisfaction

and spiritual fulfillment, as well as a creative outlet.

Being a figurative and

representational painter, myself, one of my main questions

to Raines was how she came up with her free form, asymmetrical

designs. She originally learned to draw out her designs first

by making a cartoon, a preliminary, finished sketch, which

gets pinned to the loom for guidance. But as she progressed

in weaving found herself diverging from the pattern. She enjoys

the organic detours and mysterious results of this intuitive

and unplanned process. And thus she began weaving free-form

designs without the aid of a preliminary pattern. However,

Raines picks the color scheme before she begins. Yet she does

not

limit herself from adding additional colors and fibers as

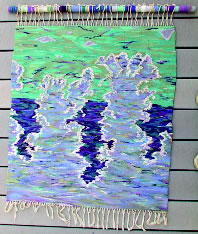

her tapestry progresses. Such is the case for her tapestry

weaving entitled “Dreaming”. In “Dreaming”,

Raines begins the weaving using hot reds, oranges, and yellows.

But as she progresses in the tapestry she intuits that the

piece calls for violets and greens and adds these new colors

for balance and harmony. The end result is a vibrant mindscape

of shapes and figures and colors that play to the active imagination. not

limit herself from adding additional colors and fibers as

her tapestry progresses. Such is the case for her tapestry

weaving entitled “Dreaming”. In “Dreaming”,

Raines begins the weaving using hot reds, oranges, and yellows.

But as she progresses in the tapestry she intuits that the

piece calls for violets and greens and adds these new colors

for balance and harmony. The end result is a vibrant mindscape

of shapes and figures and colors that play to the active imagination.

There appears to be a

narrative quality to Raines’ tapestries. Rather than

being about the design or pattern, the irregular shapes move

in a dynamic that silently expresses a story or an emotion.

The shapes, although not necessarily identifiable, speak an

archetypal language, which articulates some form of psychical

meaning. And perhaps that is what abstract art aims to achieve,

expressing some fundamental and essential meaning without

literal form or subject. In addition, Raines’ tapestry

weavings are a literal and figurative manifestation of her

relationship to Spirit. And thus, through her process of connecting

to a Divine Source through weaving, her tapestries cannot

help but represent the mode of their creation. In other words,

the underlying meaning or narrative of the tapestry weavings

express the story deep spiritual connecting.

|

Like

the Navajo, from which she learned to weave, Raines appreciates

weaving as a holistic process, combining mind, body, emotions

and spirit into the craft. The art of weaving express her

self, her story and her environment. For example, Raines began

working on “ Ciaramallow’s Dream” while

she lived at the ocean. The colors and the forms started out

as ocean waves: the blues and purples smeared together like

the many colors of the ocean and the interplay of light. Wave

forms appeared on the tapestry in the form of white, bubbling

crests. In mid-tapestry, Raines moved to the Southwest, where

she continued the tapestry. A transformation happened, however,

and her

Like

the Navajo, from which she learned to weave, Raines appreciates

weaving as a holistic process, combining mind, body, emotions

and spirit into the craft. The art of weaving express her

self, her story and her environment. For example, Raines began

working on “ Ciaramallow’s Dream” while

she lived at the ocean. The colors and the forms started out

as ocean waves: the blues and purples smeared together like

the many colors of the ocean and the interplay of light. Wave

forms appeared on the tapestry in the form of white, bubbling

crests. In mid-tapestry, Raines moved to the Southwest, where

she continued the tapestry. A transformation happened, however,

and her  waves

began to morph into dancing figures like Kachina and the tapestry

took on a whole new appearance, reflecting Raines’ internal

and external transition to a new environment. The art and

process of weaving gives Raines a lot of pleasure. The actual

weaving is simple to learn and therefore the process is calm,

rhythmic and meditative. Raines added that in the process

of weaving and creating she feels most connected to God or

to a Higher Order. And therefore, weaving gives her satisfaction

and spiritual fulfillment, as well as a creative outlet.

waves

began to morph into dancing figures like Kachina and the tapestry

took on a whole new appearance, reflecting Raines’ internal

and external transition to a new environment. The art and

process of weaving gives Raines a lot of pleasure. The actual

weaving is simple to learn and therefore the process is calm,

rhythmic and meditative. Raines added that in the process

of weaving and creating she feels most connected to God or

to a Higher Order. And therefore, weaving gives her satisfaction

and spiritual fulfillment, as well as a creative outlet. not

limit herself from adding additional colors and fibers as

her tapestry progresses. Such is the case for her tapestry

weaving entitled “Dreaming”. In “Dreaming”,

Raines begins the weaving using hot reds, oranges, and yellows.

But as she progresses in the tapestry she intuits that the

piece calls for violets and greens and adds these new colors

for balance and harmony. The end result is a vibrant mindscape

of shapes and figures and colors that play to the active imagination.

not

limit herself from adding additional colors and fibers as

her tapestry progresses. Such is the case for her tapestry

weaving entitled “Dreaming”. In “Dreaming”,

Raines begins the weaving using hot reds, oranges, and yellows.

But as she progresses in the tapestry she intuits that the

piece calls for violets and greens and adds these new colors

for balance and harmony. The end result is a vibrant mindscape

of shapes and figures and colors that play to the active imagination.