|

| Doc Julia McHugh, Curator of Paleontology at the Museum of Western Colorado, Fruita, finds no burden in shouldering a large dinosaur bone. |

There is a dual theme to the current (July-Oct) People in Paleo series. The first is that we have now featured four consecutive Museum of Western Colorado (MWC) curators, so if this were a 4 x 4 relay our current heroine, Doc. Julia McHugh would be the anchor leg. Second is that they have all worked on the often-mentioned Rabbit Valley dinosaur dig (Mygatt-Moore Quarry). There many of the similarities end. Julia breaks the MWC mold. She is not yet another dino devotee of the male persuasion, or one that escaped from MWC to Utah. Rather her paleo portfolio tells us she did her early research on amphibians from the Permian Period and the Early Triassic, and from exotic locations in southern Africa. In case you’re not a fossil amphibian expert, this was before those giant Jurassic dinosaurs, especially the sauropods came lumbering on the scene to hog the limelight. There were various “ages” of fish, amphibians and pre-dinosaurian reptiles, before the age of dinosaurs, and back then the amphibians were different, and in some cases scary: these were pre-frog days before those cute, leggy, hoppers evolved to enliven today’s nature documentaries, and perhaps even your home aquarium.

|

| A large and very expensive amphibian fossil from Germany: consult your bank manager! |

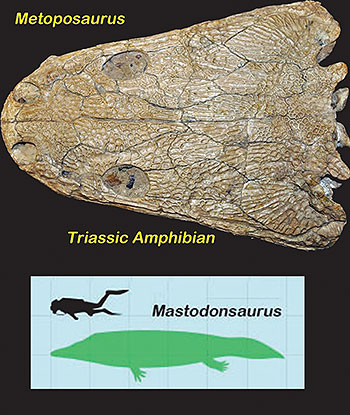

Back in those dark prehistoric days at least one Permian (280 million-year-old) salamander-shaped amphibian from Germany was almost six feet long. Get a bigger aquarium, and a bank loan: the fossil was priced at $295,000! As Julia will tell you there’s value in ‘them thar’ amphibians! Not just for the insights they give into evolution from fish to reptiles as the transitioned from water to land, but also as today’s sensitive barometers of the health of aquatic ecosystems. Among the large amphibians that survived into the Triassic one named Metoposaurus is quite well known, with a broad flat skull. Besides being up to 10 feet long in some cases, and among the top predators, some were even larger, they are often found in large concentrations where many are thought to have perished in muddy pools that dried out. Triassic aquatic ecosystems had their ups and downs.

|

| Skull of one the of better-known large amphibian fossils (Metopopsaurus) from the Triassic. This animal could grow to 10 feet long with a 2 foot-long skull. However, the even larger 20 foot-long Mastodonsaurus with six-inch-long teeth would have made Triassic swimming very hazardous. |

I have called Julia a “deep dive” detective, not because she has been diving with amphibians, as she might wish to, but because she has continued exploring the depths of the Jurassic underworld at Rabbit Valley. Remember the ~2500 bones found there? (Happenings Sept 2022). Well, they didn’t just get buried for us to find untouched. Besides dying in various ways and having their skeletons broken up by erosion, trampling and scavenging: 1/3 of bones have theropod bite marks, the decaying remains provided abundant food for insects and other invertebrates that would be impossible to find if it were not for the traces (on 1/6th of bones) which they created when nibbling on, or perhaps we should say “decomposing,” this rich source of organic material. Today, if you are inclined to clean flesh off a dead animal (everyone needs biological hobby) and preserve its skeleton, you get a certain type of beetle (a dermestid) to do the job for you (in a sealed container, unless you want your possessions consumed). Similar beetle types, and others, were already at work in the Jurassic and they left subtle traces, like signatures or fingerprints. Believe it or not, as Julia and colleagues made their deep dive into the underworld of death, decay and decomposition they identified a half dozen pits, furrows, boreholes and “bioglyphs” (some even with formal Latin names) speaking of a once “rich and thriving” living subterranean ecosystem. Just as your CSI dramas inform you of the ways that postmortem decay of bodies helps with determining the time of death, paleontologists can begin to tell us how long these dinosaur bones were buried (probably several years) while the decomposers went to work leaving their characteristic traces. Just in case you think paleontologists have no imagination or no stomach for putrefaction, one of Julia’s papers has a gory reconstruction of, and I quote, “an Allosaurus feeding on a rotting bug infested carcass.” As I said everyone needs a biological or paleontological hobby!

|