Southeastern Utah is internationally known for the beauty of its canyons and red rock deserts, its unique high desert ecosystems, and its ample recreational opportunities from mountain biking to hiking to four-wheel driving and beyond.

|

| Pure copper plates produced at the Lisbon Valley Mine. Photo courtesy of LVMC. |

The area also has a long history of mining and mineral development. Rich uranium deposits in the region earned Moab the nickname of the “Uranium Capital of the World” during the 1950s, when literal rags-to-riches stories such as Charlie Steen’s discovery of the Mi Vida Mine captured the nation’s imagination. Important potash deposits have been mined south of Moab since the 1960s. Southeastern Utah also contains oil and gas resources and even significant copper deposits.

Copper is perhaps the least known of the area’s mineral riches, but the mine producing the purest copper in the United States is located about 40 miles southeast of Moab in Lisbon Valley. Copper prospecting in Lisbon Valley dates back to the 1890s, and some copper production occurred in the area prior to the development of the current Lisbon Valley Mine in 2006.

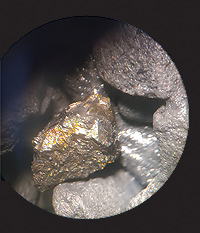

|

| Microscopic view of a small chalcopyrite crystal, one of the ore minerals at the Lisbon Valley Mine. Other ore minerals include chalcocite, bornite, covellite, azurite, and malachite. Photo courtesy of LVMC. |

On the Colorado Plateau (the general Four Corners region), copper has sometimes been found in association with uranium, but the deposit being mined by Lisbon Valley Mining Company, LLC (a wholly owned subsidiary of LV Copper Corp.) contains nearly pure copper mineralization. The overall geologic story of uranium and copper deposits on the Colorado Plateau has many similarities: metal-rich minerals were precipitated out of circulating fluids to form ore bodies long after the deposition of the sedimentary rocks in which they are found. In Lisbon Valley (which has also been an important uranium mining area), the copper-bearing saline fluids were much younger and had a different overall solution than the uranium-bearing ones.

The ore body at the Lisbon Valley Mine is a sandstone-disseminated copper deposit meaning that tiny copper minerals are dispersed between and among grains throughout the sandstone layers. The ore is located in sandstone beds in two rock layers (formations to geologists): the Burro Canyon Formation and the Dakota Sandstone (also known as the Naturita Formation). The Burro Canyon Formation contains sandstone, pebbly conglomerate (a rock made up of gravel), mudstone, and limestone deposited by rivers, in floodplains, and in lakes. The

|

| Drill core samples showing the host sandstone and conglomerate that contain copper mineralization at the Lisbon Valley Mine. Photo courtesy of LVMC. |

Dakota (Naturita) Sandstone is a bit younger than the Burro Canyon and was deposited near the edge of an inland sea (the Western Interior Seaway) about 100 million years ago. Both rock layers contain a variety of rock types, but the copper ore is only found in the sandstone and conglomerate beds within them.

The copper deposits are found adjacent to faults (surfaces along which blocks of the earth’s crust have moved relative to one another) including strands of the Lisbon Valley fault as they provided conduits for the movement of copper-bearing saline fluids. The Lisbon Valley fault is somewhat analogous to the Moab Fault. Both faults flank salt anticlines formed by the upwelling of salt deposits in the Paradox Formation in the subsurface. Salt is plastic (it can flow under the pressure of overlying rocks) and is less dense than other rocks, so it flows up, folding and doming the overlying rocks (forming anticlines). Closer to the surface, salt dissolves in groundwater, causing the axes of anticlines to collapse forming valley-like depressions.

|

| The Centennial Pit at the Lisbon Valley Mine. The Burro Canyon Formation and Dakota Sandstone, the two copper host units, are located to the left of the fault. Faults like this one are strands of the Lisbon Valley fault and were conduits for movement of copper-bearing fluids. |

Briny fluids from the Paradox Formation moving up Lisbon Valley fault picked up copper from other sedimentary rocks where it was at very low concentrations. When the fluids met the Burro Canyon and Dakota layers, small bits of organic material (in worm burrows, as low rank coal, or other detrital material) and hydrocarbons in them caused copper minerals to precipitate. These layers have high porosity and permeability allowing fluids to flow within them and are capped by a shale layer that the fluids couldn’t travel through, both factors that aided the concentration of copper minerals. Ore grades at Lisbon Valley Mine reach as high as 5% copper.

The Lisbon Valley Mine is the only sandstone-hosted copper deposit producing in the western hemisphere. The mine is currently utilizing traditional open-pit techniques. After blasting and transport, ore is crushed and spread onto a heap leach pad where a weak acid solution dissolves the copper. Copper-bearing fluids from the leach pad are then processed and mixed with other fluids which are sent to an electrowinning plant that produces high purity copper plates through electroplating.

The Lisbon Valley Mine produces 500,000 pounds per month of 99.999% pure copper cathode that is used for wiring, electronics, and green energy applications. The mine is a zero discharge facility and the pits are backfilled as mining progresses. Lisbon Valley Mining Company also practices concurrent reclamation meaning that disturbed areas are regraded to their original slopes and revegetated.

The story of the Lisbon Valley Mine is one more example of the interplay between geology and human activity throughout canyon country.

Special thanks to Lisbon Valley Mining Company and the Moab Festival of Science for inviting the public to an excellent tour of the mine in September 2023. Additional thanks to Alysen Tarrant, LVMC Environmental Manager.

|