|

| Flash flood flowing into the Colorado River. Photo courtesy of Susan Baffico |

Most of the time, our planet seems to be a static place, at least in the geologic realm. The cliffs above Moab, the arches in Arches National Park, and the views of the Colorado River from Dead Horse Point State Park seem the same from day to day, year to year, decade to decade, and century to century. Geology seems unchanging, like the rocks and landforms of canyon country. And even when people envision geologic processes, they tend to think of ones that may occur at a glacial pace (both literally and figuratively) or that take place over the arc of deep time such as what happens when the receding of an ancient sea is followed by the development of sand dunes in an arid climate.

But flash floods are sudden, dramatic, and awesome geologic processes that reveal the active nature of our active Earth. In an instant, a dry desert wash may turn into a raging, frothing, and powerful torrent that topples trees, erodes banks, and transports boulders and cobbles downstream. These boulders strike one another as they bounce along a streambed, emitting sharp percussive clacks and literally making the ground shake. Flash floods can make waterfalls appear over what had been dry cliff walls moments before. They also present one of the greatest geologic hazards in Utah.

|

| Flash flood waterfall near Grandstaff Canyon. Photo courtesy of Susan Baffico |

A Flash flood is a specific type of flood that occurs within a short time period (within six hours or less) of heavy rainfall or as a result of a collapse of a natural or man-made dam. River (or regional) flooding is the other major type wherein larger rivers experience slower rises in water levels due to either excessive precipitation or snowmelt. River floods typically crest and recede at relatively slow rates and over long periods of time and impact large regions. In contrast, flash floods may be extremely localized, sudden, and quick.

Canyon country is particularly vulnerable to flash flooding for several reasons. First, the arid climate leads to dry compact soils that do not absorb water well. Further, the lack of vegetation, which absorbs water and slows and reduces runoff, also contributes to flash flooding. Significantly, the large areas of exposed bedrock, such as the sandstone domes in Arches National Park or along the Slickrock Trail in Sand Flats Recreation Area, absorb almost no water during rain events. Instead water begins the flow along the surface almost instantaneously. Finally, the steep slopes and cliffs present throughout the region means that water flows downhill fast, gaining momentum and speed.

Southeastern Utah is also impacted by the North American Monsoon. A monsoon is a seasonal change in regional wind directions. This monsoon pulls tropical moisture north from the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf of California during the late summer months, leading heavy thunderstorms typically in July, August, and September. As a result, flash floods are most common during the summer, but they may occur any time of year.

Rainfall intensity, duration, and storm totals may also greatly impact flash flooding. More rapid rainfall rates, longer duration storms, and greater rainfall amounts are all more likely to induce a flash flood than lessor values.

Flash floods present some of the greatest dangers in canyon country, especially since they are unpredictable and because rain upstream may cause a flash flood in an area where no rain has fallen. Moving water can be deceptively powerful: depths of only six inches may knock a person off of their feet and depths of two feet can carry away a SUV or pickup truck. Water flowing in what are normally dry wash bottoms may strand hikers and/or wash out roads.

|

| Water flowing off of slickrock during a brief rainstorm. |

Slot canyons, which are extremely narrow canyons with a depth-to-width ratio of at least 10:1, can be especially hazardous because the sculptured sandstone walls (that may be vertical or even overhanging) may not allow hikers to climb out of them in the case of a flash flood.

Check the weather forecast and/or inquire in visitor centers or other local information centers before venturing out, especially when traveling in a slot canyon or washes. During the summer months, the National Weather Service issues a daily flash flood potential warning for the national parks and other areas with popular slot canyons in southern Utah.

While they can be dangerous, flash floods are an integral part of the red rock country near Moab. Much of the erosion that shapes the landscape occurs during flood events. Native vegetation growing along streams and washes is adapted to flash flooding as it is a natural part of these ecosystems.

When viewed from a safe distance and location, witnessing a flash flood may be one of the most breathtaking experiences that can be had in southern Utah because it provides insight into the geological forces that have carved this beautiful place.

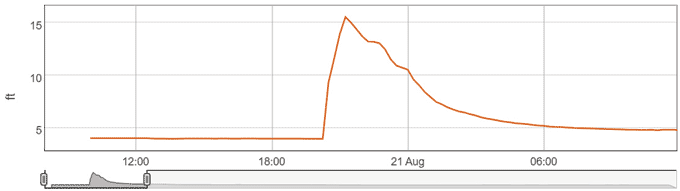

Intense rainfall just east of Moab on August 20, 2022 caused significant flash flooding in Mill and Pack creeks through town. Automated National Weather Service gages in Spanish Valley recorded rainfall amounts of 1.42 and 1.71 inches in an hour’s time. Mill Creek in Moab rose more than 11 feet in hour and overtopped roadways in several places and damaged homes and businesses. |

|

| Clean up after the Mill Creek flash flood on 300 East. |

|

| River gage at Mill Creek in Moab showing the rate and the amount that the water level increased during the flood. Credit USGS |

|