The natural world abounds with lookalikes. Many different wildflowers look very similar, especially the yellow composites. Cedar and juniper trees have many traits in common, and the several species of small lizards found near Moab are hard to tell apart. So many sparrow species are so hard to tell apart that some casual birders simply call them “LBJs” for “little brown jobs.”

Likewise, canyon country contains some rock layers (formations to geologists) that can be hard to distinguish from one another because their rock type(s), colors, thickness, and other characteristics are very similar to other layers found here.

Rock layers are unique records of specific time periods in geologic history when certain types of sediment were deposited in specific ancient environments, whether it was in sand dunes, on floodplains, or underneath ocean waters.

|

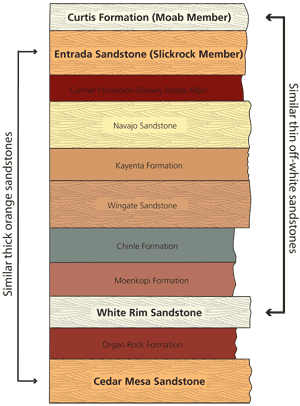

| Stratigraphic column for southeastern Utah showing two of the pairs of easily confused eolian sandstones. |

This Geology Happenings column is the second one on rock layers that get confused with other layers. Last month’s article discussed layers with similar names and two lookalike formations that erode to striped slopes. It can be found online in the Article Archive at www.moabhappenings.com. This article focuses on three pairs of sandstones that are geologic doppelgangers for each other, as well as some of the challenges that exist when two formations that look alike are stacked one upon the other.

Rock Layers that Look Similar

As a general rule, rock layers with similar depositional environments look at least somewhat alike because they contain the same types of sediments and were formed in analogous ways, whether it be sand transported by rivers or mud deposited on tidal flats. The three pairs of doppelganger are all eolian in origin, meaning that they were deposited in sand dunes. But each of these dunefields formed at a different time in geologic history, and each had unique attributes; some were small dunes found in a limited geographic area and others were extensive dunefields found along the coast of an inland sea.

Arches National Park and the Needles District of Canyonlands National Park are two of the most iconic landscapes found in southeastern Utah. Each has their own rock star: The Entrada Sandstone in Arches, and the Cedar Mesa Sandstone in the Needles. These two layers mostly consist of orange sandstone, although sometimes they have lighter color bands in them. They both erode to sandstone spires, ridges, and domes. They look a lot alike, so much so that the first time I went to Needles, I thought that the sandstone exposed there was the Entrada.

However, the two layers are more than 110 million years apart in age. The best way to tell them apart is to note their geologic context; that is, the layers that are above and below them. A stratigraphic column is a chart showing the sequence of rock layers found in any given area, and they can serve as a key that helps to identify lookalike layers.

Like the Cedar Mesa-Entrada pair, the White Rim Sandstone and the Moab Tongue Member of the Curtis Formation appear nearly identical to one another. They are thin off-white sandstones that are particularly resistant to erosion and sometimes hold up white-capped rock spires. These two layers also can best be differentiated by learning where they fit in the rock chart.

|

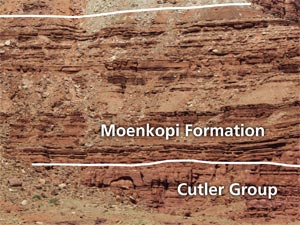

| The Cutler Group is found near Moab instead of the Cedar Mesa Sandstone, Organ Rock Formation, and White Rim Sandstone shown in the rock chart. |

The Wingate Sandstone is one of the most recognizable rock layers found in southern Utah. It forms many miles of dark red palisade-like cliffs with vertical fracturing (jointing) on the Colorado Plateau.

The rock layer that holds up the buttes and spires of Monument Valley along the Utah-Arizona border looks just like the Wingate, but it is the DeChelly Sandstone, a completely different layer. The DeChelly Sandstone is not found in southern Utah as the dunefield it was deposited in didn’t extend this far north. It is older than the Wingate and is roughly the same age as the White Rim Sandstone.

Rock Layers that Look Like Adjacent Layers

The hardest rock layers to tell apart are similar-appearing ones that are found directly on top of one another. Formations are defined based on more than just rock type, but also age, fossil content, and other characteristics. Sometimes there are periods of missing time (unconformities) between adjacent layers. Layers will have a recognizable contact (boundary) between them that may show evidence of erosion or have other identifying features.

The Cutler Group and Moenkopi Formation are two adjacent red layers found near Moab that they are very hard to tell apart. A significant unconformity of about 20 million years separates them, and they were deposited in different environments: the Cutler consists of sediments transported from an ancient mountain range to the northeast, and the Moenkopi was primarily deposited in tidal flats. The contact between them can be subtle, but the Cutler usually has a brighter red shade and the Moenkopi has a more chocolate hue and thinner layers.

|