Even people with the most casual acquaintance with Moab’s geology, both travelers and local residents alike, know the names of at least some of southeastern Utah’s most prominent rock layers: the Entrada Sandstone, the Morrison Formation, the Wingate Sandstone, and the Mancos Shale. These layers make up the area’s distinct scenery and record the area’s geologic history: the natural arches (mostly in the Entrada Sandstone) of the eponymous national park, the famous dinosaur fossils found in the Morrison Formation, the soaring red cliffs of the Wingate Sandstone above Moab and along the Colorado River, and the stark gray cliffs comprised of the Mancos Shale north of I-70. Even people with the most casual acquaintance with Moab’s geology, both travelers and local residents alike, know the names of at least some of southeastern Utah’s most prominent rock layers: the Entrada Sandstone, the Morrison Formation, the Wingate Sandstone, and the Mancos Shale. These layers make up the area’s distinct scenery and record the area’s geologic history: the natural arches (mostly in the Entrada Sandstone) of the eponymous national park, the famous dinosaur fossils found in the Morrison Formation, the soaring red cliffs of the Wingate Sandstone above Moab and along the Colorado River, and the stark gray cliffs comprised of the Mancos Shale north of I-70.

What people may not realize that the formal system of naming rock layers is somewhat akin to the binomial system for naming living organisms in biology. Although geology, thankfully, does not have not separate common and scientific names. (Thankfully, at least to people like myself who can’t pronounce Latin names like Phrynosoma hernandesi, aka, the short-horned lizard.)

In biology, species is the principle taxonomic unit. In geology, formation is the principle unit of stratigraphy (the study of rock layers). A formation is a body of rock identified by its characteristics and that can be differentiated from other rock layers. Formations are made up of specific type(s) of sedimentary rock (e.g., sandstone, limestone, or shale) or a mixture of different rock types. Formations are typically deposited in specific environments during a unique interval of geologic time.

|

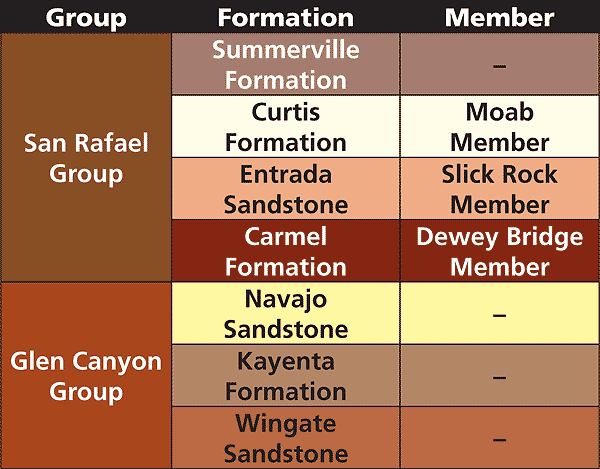

| In the Moab area, the San Rafael Group contains four formations, and the Glen Canyon Group contains three formations. The Carmel, Entrada, and Curtis formations each contain one defined member, while the other formations in these two groups do not have any members defined in this region. |

A name of a stratigraphic unit consists of a two parts: a geographic name (derived from the region where it is found) and a designation of rock type or stratigraphic rank. The North American Stratigraphic Code sets forth the rules for naming rock layers and specifies that geographic names are derived from permanent features shown on topographic or other maps, and that the geographic name must be unique (e.g., two different rock layers cannot have the same geographic name). Formations must be defined in the formal scientific literature with published descriptions usually describing a unit’s contacts (boundaries) with other rock layers and defining a stratotype, which is the standard for that rock unit and serves as the same role as a type or reference specimen does in biology.

Biology has a full system of taxometric ranking (species, genus, family, etc.) that describes the relationships that species have to one another. Stratigraphic nomenclature has a similar ranking system in that formations may be part of groups, but only when there are relationships between formations. For example, the Glen Canyon Group contains three formations: the Wingate Sandstone, the Kayenta Formation, and the Navajo Sandstone. These units were deposited during the Jurassic Period when the depositional environment changed from an arid sand dune system to one dominated by sandy river systems and then back to a sand dune system when arid conditions returned. Although the environment changed during the 15 million years or so when the three formations were deposited, there was continuous deposition during this interval and the overall geography of the four corners region was basically the same.

|

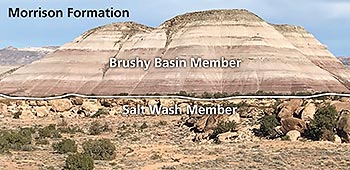

| The Salt Wash and Brushy Basin members of the Morrison Formation are examples of members that are obviously different from one another. The Salt Wash Member was deposited in stream channels, and the Brushy Basin Member was deposited on broad floodplains. |

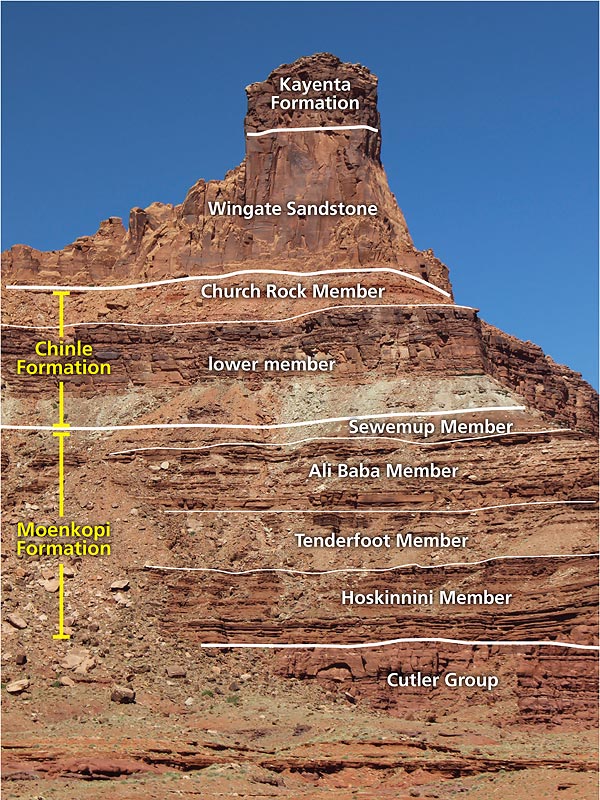

Other formations stand alone in that they are not part of groups. The Moenkopi and Chinle formations may be adjacent to one another and look somewhat alike as they both form slopes made up of thin beds, but neither belong to a group, much less to the same group. These units are separated by a major time gap of approximately 30 million years which also corresponds to an interval when a significant change in the tectonics of western North America occurred.

In turn, formations may (or may not be) broken up into smaller subunits called members. Members are defined when there is a distinctive rock type (called a facies) within a formation, particularly when it is restricted to a portion of the area where that formation is found. Because members are frequently defined based on different facies, a formation may contain different members from one area to the next, e.g., different members are present in the Moenkopi Formation in the Capitol Reef National Park area than are found near Moab.

Books provide another illustrative analogy for the relationships between groups, formations, and members. Books are like formations in that they are a fundamental unit (of literature). Books that are related to each other are issued together as volume sets. And books are sometimes divided into chapters.

There are four different groups, 18 different formations, and many members exposed in the cliffs and canyons surrounding Moab. Getting to know Moab’s rock layers, whether they are grouped into groups or dismembered into members, can deepen your understanding of the area’s geologic history.

|