|

| Collecting an sample for dating a Colorado River terrace across the river from Dead Horse Point. Photo courtesy of Natalie Tanski. |

Evidence that canyon country is geologically young is abundant all around Moab. The overall high elevation, steep slopes covered by rocky talus, miles upon miles of cliffs, and rivers with steep gradients flowing through deep canyons all point to a young landscape that is rapidly evolving and changing. But until fairly recently, geologists had few techniques that enabled them to answer a fundamental question: “How young is young?”.

Obtaining the age of a landscape is inherently more difficult than determining the age of a rock. Some types of rocks, particularly those that are igneous in origin (e.g., crystallized from molten material), contain minerals that can act as geologic clocks. These clocks depend on the decay of radioactive elements since it occurs at known rates. Geologists are thus able to analyze certain minerals to obtain the concentrations of a radioactive parent isotope and its stable daughter element to determine when it crystalized based on the radioactive element’s half-life. Geologists can also use these radiometric dating techniques on sedimentary rocks that contain volcanic ash beds or minerals (like glauconite or calcite) that grow at the time of deposition to measure when they were formed.

But landscape features like cliff faces or river deposits cannot be dated using radiometric techniques since the minerals they contain are much older than the landscape feature or deposit themselves. Some river deposits contain organic material that can be dated using the carbon-14 radiometric technique, but only when organic material is present and is less than 50,000 years old (because carbon-14 has a short half-life). Therefore, scientists have to find other ways to obtain information that helps constrain the age of Moab’s spectacular terrain.

|

Natalie has freshly exposed a sand lens within a river deposit near the Poison Spider Trail (off Potash Road) to collect a sample for luminescence dating. All pits are filled in and smoothed over after collecting, and sample collecting is permitted by the BLM.

Photo courtesy of Natalie Tanski. |

Understanding the history and evolution of the Green and Colorado rivers is essential for deciphering the origin and age of southeastern Utah’s landscape because they are the important erosive agents and set the local base level. A group of researchers led by Joel Pederson and Tammy Rittenour of the Department of Geosciences at Utah State University in Logan are studying stream terraces (floodplain and channel deposits that are left perched above the current river level) to learn about how and when the current landscape came to be.

They are using a dating technique called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to learn when river terraces were deposited. OSL is a type of burial dating that measures when sediment was last exposed to sunlight.

The technique is based on the fact that radiation from cosmic rays and natural radioisotopes causes electrons to become trapped in the crystal structure of buried feldspar and quartz grains. These electrons escape when exposed to sunlight, resetting (bleaching) the sample. Therefore, the quantity of trapped electrons is proportional to the length of time that the sediment has been buried.

Analysis involves exposing samples to blue-green light in a dark lab to release trapped electrons which in turn emit photons of light (e.g., luminescence) which are measured. Ages are calculated using the accumulated dose of radiation (as measured via the luminescence) and the rate of the radiation dose. Labs typically run analyses on multiple small portions of each sediment sample in order to improve precision and accuracy.

|

Geologists typically collect OSL samples by pounding a hollow tube into a terrace deposit and sealing the ends so that the sediment isn’t exposed to light during collection. Material around the sample is also collected as well as elevation and other data in order to calculate the radiation dose rate needed to calculate the age estimate.

Photo courtesy of James Mauch. |

USU Department of Geosciences PhD student Natalie Tanski is studying river terraces along the Colorado River from the Portal near Moab to the confluence with the Green River in order to decipher the river’s erosion history. She has collected samples for OSL dating at many sites along the river, including near the Corona Arch Trail that were measured to be between 200,000 and 210,000 years old.

James Mauch, who earned his MS degree in geology from USU in 2018, collected OSL samples from terrace deposits along Mill and Pack creeks in order to learn how rapidly the Moab-Spanish Valley has been sinking due to salt dissolution (in the underlying Paradox Formation) over the last 200,000 years. The valley has dropped approximately 650 feet (200 meters) during that time, at an average rate of approximately 0.04 inches (1 mm) per year, which is surprisingly fast.

OSL dating is an important tool that geologists are using to better understand how canyon country came to be. The sediments in most stream terrace deposits are suitable for the technique, which is applicable for deposits that range in age from a few hundred years to a few hundred thousand years old, a time interval for which geologists have few other techniques that they can use.

Advances in OSL analyses have improved the precision of the dates and are enabling geologists to understand the history of rivers and landscapes with a level of detail that previous researchers couldn’t have dreamt. Geologists are now not only answering the “how young?” questions, but also “how fast?,” and gaining more comprehensive insights into how fluvial erosion and other geologic processes have yielded one of the most beautiful places on Earth here in the red rock desert surrounding Moab.

|

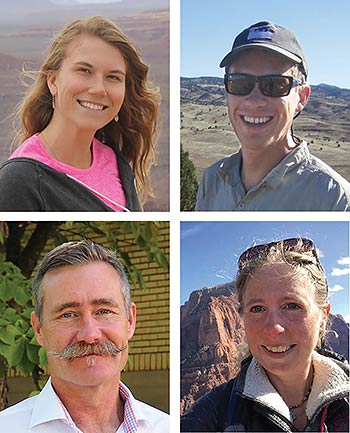

Clockwise from upper left: Natalie Tanski, James Mauch, Tammy Rittenour, and Joel Pederson.

Photos courtesy of Utah State University. |

|