GEOLOGY HAPPENINGS February 2021 |

||||||||||||

| The Heroic Age of Colorado Plateau Geologyby Allyson Mathis | ||||||||||||

Although the first reports that focused specifically on the geology of the Moab-Spanish Valley weren’t published until early in the twentieth Century, investigations into the geology of the larger Colorado Plateau played a central role in the development of the science of geology in the United States. John Wesley Powell, who led the first exploration down the Green and Colorado rivers a few years after the end of the Civil War, is the best known of a quartet of pioneering geologists who put the geology of southeastern Utah on the map. Powell, together with John Strong Newberry, Clarence Dutton, and GK Gilbert, established the primacy of geologic thought in understanding this most scenic part of the North American continent.

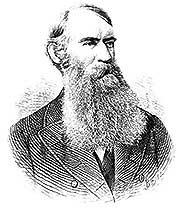

The first geologist to visit canyon country arrived a decade before Powell’s river expedition. John Strong Newberry was part of the expedition led by Captain John Macomb in 1859 that set out to locate the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers, now in the heart of Canyonlands National Park. Newberry had previous experience with Colorado Plateau geology as he was the first geologist to visit part of Grand Canyon with the Colorado River Exploring Expedition led by Lieutenant Joseph Christmas Ives in 1857 and 1858 (predating Powell by more than a decade). Macomb, like some other leaders of government-sponsored explorations in the American West, found little to recommend canyon country, writing, “I cannot conceive of a more worthless and impractical region.” But Newberry found the opposite to be true; writing that “the Colorado Plateau is to the geologist a paradise.” Newberry’s work laid the foundation for future geologic studies of the Colorado Plateau. For example, he properly deduced that fluvial erosion (or sculpting by rivers) was responsible for shaping landscapes, an idea that was not universally accepted by geologists at the time.

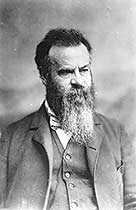

In 1869, John Wesley Powell, a one-armed Civil War veteran, self-taught geologist, college professor, and secretary of the Illinois Natural History Society, led a ragtag group of mountain men down the Green River from Wyoming, and then through Cataract, Glen and Grand canyons on the Colorado in the last great exploration in the American West. The popular account of the expedition, serialized in Scribner’s Magazine, captured the nation’s imagination, which Powell then used as a springboard to his subsequent career as a government scientist. First, he obtained Congress’ support for the Powell Survey which included a second exploration of the canyons by boat in order to obtain measurements that were lost in the initial trip, since it actually had become more of an epic of survival than a scientific exploration by the time they reached Grand Canyon. Powell later became the second director of the United States Geological Survey, which is to this day still the nation’s largest earth science agency. Despite Powell’s prowess as a geologist, his most significant scientific achievements of the Powell Survey were actually not led by Powell himself, but by Clarence Dutton and GK Gilbert, two of the era’s brightest scientific minds.

Dutton was loaned to the Powell Survey by the War Department where he served as a Captain in the Ordnance Corps. Dutton led a field team for the Powell Survey that mapped an approximately 12,000 square mile area in the High Plateaus region, extending roughly from Capitol Reef to Zion national parks. Dutton’s geologic contributions extended far beyond his studies of the High Plateaus and Grand Canyon. He was also the nation’s leading volcanologist who studied the Hawaiian volcanoes and Crater Lake in Oregon, and he published the seminal report of the great Charleston, South Carolina earthquake in 1886, which was one of the largest earthquakes to have ever occurred on the east coast.

GK Gilbert is perhaps the least known of these early scientists, but he was a geologist’s geologist who had the best scientific mind of the group. He is known as the father of geomorphology, which is the branch of science that studies the origin and evolution of landscape features. Gilbert’s work on the Henry Mountains is still considered a classic, and he also published an important study of the Lake Bonneville, the expansive Ice Age Lake of which the Great Salt Lake is just a small remnant. |

||||||||||||

|