|

|

GEOLOGY HAPPENINGS April 2020 |

At Least it’s Just Geology: The Moab Fault

by Allyson Mathis |

|

| Close-up of the Moab Fault near the Arches Visitor Center. |

In everyday life, a fault is an unattractive, unsatisfactory or defective feature, or the responsibility for a mistake or failure. But in geology, a fault is merely a fracture or crack where blocks of the earth’s crust or bodies of rock have moved relative to one another. Abrupt movements along faults cause most earthquakes, which are sudden motions or tremblings in the earth. Friction causes strain to build up along a fault until it passes a threshold, when the energy is released via slippage along the fault, causing the ground to shake, as what happened in the March 18th earthquake near Magna, Utah.

Faults may be classified by geologists as inactive, meaning that their most recent movement was during the geologic past, or active, meaning that by definition, motion has occurred during the last 10,000 years, and that they are expected to produce earthquakes in the future.

|

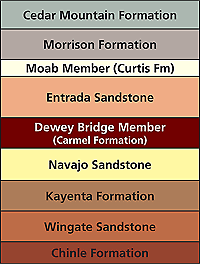

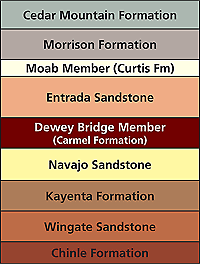

| The Moab fault near the Arches Visitor Center. The rocks on the right have been downfaulted relative to the rocks on the left. The rock chart shows that the Entrada Sandstone exposed near the visitor center is younger than (and stratigraphically sits above) the Wingate Sandstone at the top of the cliff. |

The Moab Fault is the most well-known fault in southeastern Utah, and is also one of the longest in the region. The fault’s surface trace stretches for 28 miles from near the Arches Visitor Center to the northwest near Courthouse Rock where it jogs to the west. It also extends to the southeast, where the fault is buried underneath the sediment fill of the Moab-Spanish Valley, which is actually a down-faulted block, or graben, rather than a true river valley.

The Moab Fault is different than the majority of faults in that most of its movement is related to salt tectonics versus ordinary tectonics. Tectonics concern the overall structure of the earth’s crust and the movements that occur within it. Salt tectonics are generally more local phenomena associated with the movements of thick deposits of salt that can flow plastically underneath the pressure of overlying sediments.

Salt deposits are present in the Paradox Formation underneath southeastern Utah. Upward movement of these salts, along with their dissolution by groundwater near the surface has formed the Moab-Spanish Valley, and accounts for much of the displacement along the Moab Fault. The Moab Fault dies out in the Paradox salts in the subsurface and

|

doesn’t appear to connect with deep geologic structures in the area.

The earthquake hazard from Moab Fault is low. The energies involved in salt movement are less than those in ordinary tectonic processes, and most if not all of the movement along the Moab Fault probably occurred well in the geologic past. The US Geological Survey has determined that the Moab area has a relatively low seismic hazard, with the estimated number of damaging earthquake shaking events in 10,000 years being between four and ten.

|

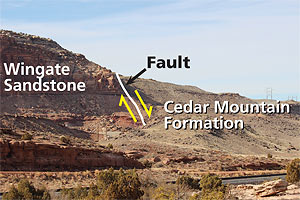

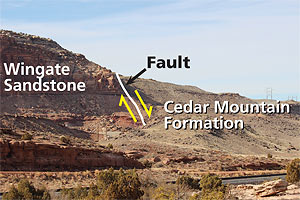

| The Moab Fault near the Cotter Mine Road. The Cedar Mountain Formation on the right has moved down relative to the Wingate Sandstone on the left. Faults can sometimes be recognized in the field where one rock layer (formation) abruptly abuts another layer in this location. |

THE GREAT UTAH SHAKEOUT

On March 18, 2020, Many residents of the Salt Lake Valley were awakened by a magnitude 5.7 earthquake near Magna, Utah. This earthquake took place within the Intermountain Seismic Belt that extends north-south from Montana to northern Arizona. This seismically-active zone is related to the stretching of the North American continent that is responsible for the Basin and Range Province in western Utah and Nevada. Geologists think that earthquakes as large as 7.5 magnitude may occur in the Intermountain Seismic Belt in Utah, creating significant risk to the approximately 2.3 million Utahns who live within it. Because of the risk that exists from damaging earthquakes in the state an earthquake preparedness drill, the Great Utah ShakeOut, occurs in April each year. This year’s drill is scheduled to take place on Thursday, April 16, 2020. Visit www.shakeout.org/utah/ to learn more.

Regardless of whether you participate in the shakeout, all Utah residents should learn how to Drop, Cover and Hold On during an earthquake.

DROP where you are, and onto your hands and knees. This position protects you from being knocked down and also allows you to stay low and crawl to shelter if nearby.

COVER your head and neck with one arm and hand. If a sturdy table or desk is nearby, crawl underneath it for shelter. If no shelter is nearby, crawl next to an interior wall (away from windows). Stay on your knees; bend over to protect vital organs.

HOLD ON until shaking stops. If you are under shelter, hold on to it with one hand; be ready to move with your shelter if it shifts. If you don’t have shelter, hold on to your head and neck with both arms and hands.

The Drop, Cover and Hold On information is from www.shakeout.org/utah/dropcoverholdon/. |

|

|

You can read more geology articles HERE

A self-described “rock nerd,” Allyson Mathis is a geologist, informal geoscience educator and science writer living in Moab. Allyson prefers geologic faults (especially inactive ones) over those in humans, although we all have them. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

© 2002-2026 Moab Happenings. All rights

reserved.

Reproduction of information contained in this site is

expressly prohibited.

|

|