Hiking Moab area trails is one of the best ways to experience canyon country geology. This is one of a series of columns on trailside geology. Mileages were measured using a handheld GPS unit.

| Corona Arch Trail: 1.3 mile one-way from the trailhead on the Potash Road (Utah 278), about 14 miles from Moab. Elevation gain is approximately 400 feet. The hike includes a steep climb up a sandstone incline with a cable providing handholds and a short ladder. The trail ends underneath Corona Arch, but hikers who do not want to do the steep climb and ladder can see Corona Arch just before it. Hikers should always carry water, snacks, and other essentials. |

The Corona Arch Trail is one of the most popular hikes in the Moab area. Corona Arch is a 105-foot tall natural arch carved in the Navajo Sandstone, one of the most beautiful rock layers (formations to geologists) in southeastern Utah, if not the entire planet. The Navajo forms soaring domes white- to orange-colored sandstone, and contains numerous large natural arches. The Navajo Sandstone is also the “rock star” in Zion and Capitol Reef national parks, and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and plays supporting roles in Arches and Canyonlands national parks.

This trail gives hikers the opportunity to examine some of the common features in the Navajo Sandstone, including crossbedding and hanging gardens, as well as view two spectacular natural arches. The Navajo Sandstone was deposited in a massive sand dune field approximately 185 million years ago. Crossbedding consists of inclined laminations that formed on rounded dune surfaces as they migrated in the wind.

Trail Log

Trail Log

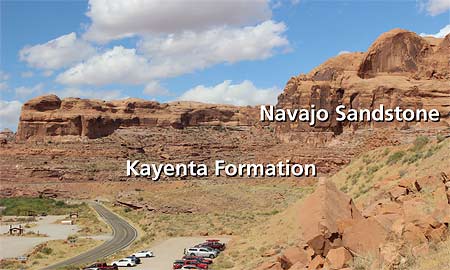

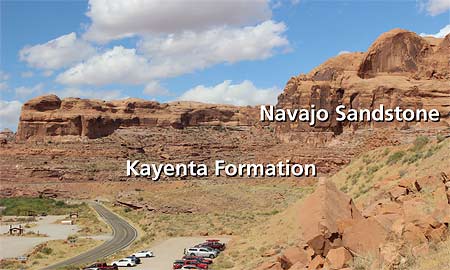

Mile 0.0 Trailhead: While most of the trail to Corona Arch is in the Navajo Sandstone, the trailhead is in the Kayenta Formation which is below the Navajo. The Kayenta Formation was deposited in a series of broad shallow rivers flowing across arid lands in what is now Utah, just prior to the time of deposition of the Navajo Sandstone. The contact, or boundary, between the Kayenta and Navajo is gradational, meaning that environments gradually changed from one dominated by sandy rivers during Kayenta times to that of a large sand dune system for the Navajo Sandstone. As the environment became more arid, layers of fluvial (river-deposited) sandstones alternated (or intertongued) with eolian (sand dune) sandstones. For graditional contacts such as this one, geologists select a particular horizon as the contact that another scientist can recognize. Here, the Kayenta-Navajo contact is defined as the lowermost massive light-colored eolian sandstone layer.

Mile 0.1: Trail register. Just ahead, the trail crosses a set of railroad tracks. The rail line serves the Intrepid Potash mine south of here. Potash (potassium chloride) is mined from deposits of evaporate minerals (including rock salt) that were precipitated in an extremely saline ocean basin.

|

| Mud cracks at location 1 |

Location 1 (0.2 Mile): Where the trail takes a sharp turn to the right, look underneath the overhang here to see an excellent example of mud cracks. Mud cracks form when sediments containing a lot of clay shrink as they dry. These have been infilled with sand from the layer above.

Mile 0.4: The trail has topped a short incline. Navajo Sandstone is all around.

Location 2 (0.6 Mile): The trail surface is on a section of Navajo Sandstone slickrock. Straight ahead and to the left are large domes of Navajo Sandstone.

To the right, look at the broad bench at an elevation slightly higher than the trail. This bench is part of a fluvial terrace capped by cobbles that were deposited by the Colorado River (see map). Terraces are remnants of a stream’s former floodplain that gets perched above the current channel after it downcuts or incises into its valley. This is the highest Colorado River terrace in this area and was deposited approximately 200,000 years ago when the river was approximately 300 feet higher here than its current elevation. (You may have noticed some of these river cobbles next to the trail during your hike that have washed down from the terraces.)

0.8 Mile: Just past a cable providing handholds for a section of slanted slickrock, look for Corona Arch straight ahead. Look for crossbedding in the Navajo Sandstone in this area.

|

| Crossbedding |

0.9 Mile: Steep climb up slickrock. Footsteps have been chipped into the sandstone, and the cable provides handholds, but be sure to turn around if you aren’t comfortable ascending and descending here. Look for crossbedding in the Navajo.

Location 3 (1.15 Mile): Bowtie Arch is to the left. Bowtie is a pothole arch. Potholes are depressions in slickrock surfaces caused by the dissolution of the cement that holds together sand grains. Pothole arches form where a pothole intersects an alcove or overhang cut into a cliff face. Note the hanging garden is located underneath the arch. Hanging gardens are springs or seeps that emerge from the surface of cliff faces and are adorned with vegetation growing on vertical or overhanging surfaces.

Location 4 (1.3 Mile): The trail ends underneath Corona Arch. Corona Arch formed in a fin, or thin rib, of sandstone between small drainages in front of and behind the arch. Weathering and erosion created the opening in the thin rock ridge.

|

| Map of the Corona Arch Trail. Imagery is from Google Earth. |

Trail Log

Trail Log