Geology HAPPENINGS August 2019 |

||||

| The La Sal Mountains: A Geology Story of Fire, Not Ice by Allyson Mathis |

||||

The cool temperatures in the higher elevations of the La Sal Mountains beckon both residents and tourists alike during the summer. Alpine meadows with splashes of wildflowers, dark green fir trees, alpine lakes and remnant snow fields provide a respite from the scorching heat in red rock country. Likewise, heavy snowfall in the higher elevations provides a multitude of opportunities for winter sport enthusiasts.

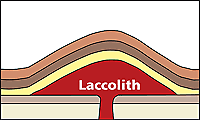

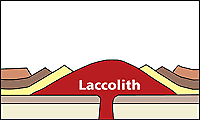

Besides providing the highest elevations in southeastern Utah at more than 12,000 feet, the La Sal intrusions are known geologically for their distinctive shape. Laccoliths are domed or mushroom-shaped intrusions with flat bottoms and domed tops. Laccoliths form when magma is injected between flat layers of sedimentary rock and force the overlying layers to bulge above the mass of igneous material. The term laccolith was introduced in 1875 by geologist G.K. Gilbert who studied the Henry Mountains. While there is no evidence of volcanism that happened in association with the emplacement of the laccoliths in the La Sals, it is possible that eruptions did occur. The La Sals magmas were injected to very shallow levels of the earth’s crust, crystallizing at depths between 1.2 and 3.7 miles (as a contrast, crystallization depths of the granites in the Sierra Nevadas were as deep as 19 miles). In fact, the appearance of some igneous rocks found in the La Sal Mountains so closely resemble volcanic rocks that some geologists have used volcanic rather than plutonic nomenclature when describing them.

The La Sal laccoliths were intruded largely into rocks of the Morrison Formation and Mancos Shale (in fact the top of Mt Peale is in the Morrison) when thousands of feet of younger sedimentary rock would have been above them. Given the massive amounts of erosion that have occurred in the area, any volcanic rock or ash deposits associated with the La Sals would have been eroded away along with the overlying sedimentary rocks. Whether or not volcanic eruptions took place along with the intrusions is something that we may never know. Dates that have been recently published in the scientific literature provide a more precise indication of when the intrusions were emplaced. A paper published in 2017 in the journal Geosphere obtained a crystallization age of 29.1 (±0.3) million years ago on a sample collected on the flank of Mt. Peale. And a paper in the American Journal of Science just published in July includes a date of 27.7 (±0.2) for North Mountain and Round Mountain. Previous research had placed the timing of the La Sal intrusions within the range of 25 to 31 million years before present.  The La Sals formed well after the youngest sedimentary rocks still present near Moab were deposited, yet long before the Colorado River established its course during the last 6 million years or so, and especially before the evolution of the modern Moab landscape which occurred within just the last 1.5 million years (see the May issue of Geology Happenings in the article archive at www.moabhappenings.com to learn more). The La Sals formed well after the youngest sedimentary rocks still present near Moab were deposited, yet long before the Colorado River established its course during the last 6 million years or so, and especially before the evolution of the modern Moab landscape which occurred within just the last 1.5 million years (see the May issue of Geology Happenings in the article archive at www.moabhappenings.com to learn more). Together with the Abajo and Henry Mountains (also laccoliths that formed at about the same time), the La Sals provide important data points during an interval in southern Utah’s geologic history when relatively little is known. They help tell the story about how the Colorado Plateau area, which had been a basin where sedimentary rocks had been deposited for hundreds of millions of years, turned into an erosional landscape of canyons and mesas at high elevation. The La Sal Mountains remain a place to beat the heat in the summer, but also a place to think about geologic change through time, and to ponder specific questions whether if volcanic eruptions may have accompanied the emplacement of geologic fires below.

|

||||

|

||||

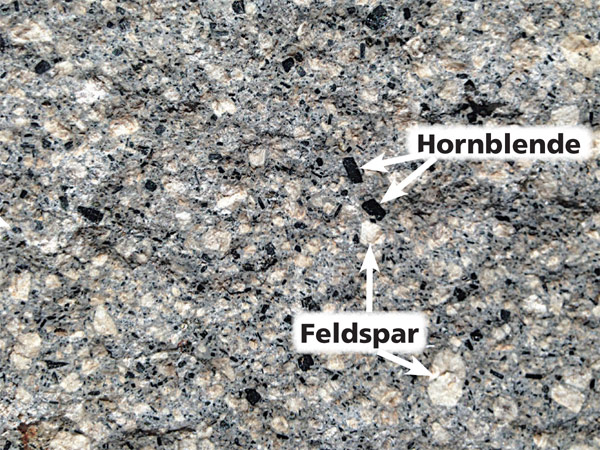

Igneous rocks are crystallized from melted or molten rock (magma). Magma can erupt at the earth’s surface, forming lava flows and volcanoes, but it also can be crystallized within the earth’s crust to become intrusive or plutonic rocks. Igneous rocks are crystalline, usually appearing very different from the sedimentary sandstones and shales found near Moab. The igneous rocks (generally a type of rock called diorite) in the La Sals are speckled in salt and pepper colors (with much more light-colored feldspar than black hornblende) with individual crystals sometimes reaching a half an inch in size.

Igneous rocks are crystallized from melted or molten rock (magma). Magma can erupt at the earth’s surface, forming lava flows and volcanoes, but it also can be crystallized within the earth’s crust to become intrusive or plutonic rocks. Igneous rocks are crystalline, usually appearing very different from the sedimentary sandstones and shales found near Moab. The igneous rocks (generally a type of rock called diorite) in the La Sals are speckled in salt and pepper colors (with much more light-colored feldspar than black hornblende) with individual crystals sometimes reaching a half an inch in size.