| Geology HAPPENINGS July 2019 | ||||||||

| John Wesley Powell: Geologist “If he can only study geology he will be happy without food or shelter” by Allyson Mathis |

||||||||

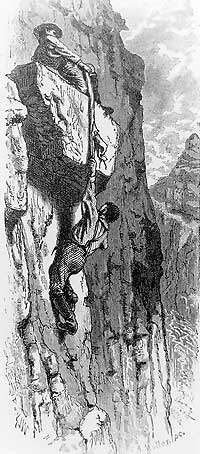

Powell’s purpose for the exploration of the Green and Colorado rivers was purely scientific, as stated in a letter to General Grant asking for permission to draw army rations to support his expedition. Describing his objective, Powell wrote that the “Grand Canyon of the Colorado will give the best geological section on the continent.” Powell’s party of ten men left Green River, Wyoming in four wooden boats on May 24, 1869, officially under the auspices of the Illinois Natural History Society, of which Powell was secretary. By the time they reached the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers on July 17th, now in the heart of Canyonlands National Park, they had traveled 538 miles, lost one of their boats and either lost or used most of their rations. There, they spent several days re-caulking their boats, drying the remaining rations, and repairing instruments before continuing downstream.

“The men are uneasy and discontented and eager to move on. If the major does not do something soon, I fear the consequences, but he is contented … If he can only study geology he will be happy without food or shelter, but the rest of us are not afflicted with it to any alarming extent.” Powell received a hero’s welcome after his successful passage through Grand Canyon (although it was not without tragedy as the fate of three men who had left the expedition remains unknown). His triumph led directly to full federal support of the Powell Survey and to his second exploration of the Colorado River. Major scientific publications soon followed. First, Report of the Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and Its Tributaries in 1875, and then Report on the Geology of the Eastern Portion of the Uinta Mountains in 1876. His Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States argued for conservation and careful planning of land use in the west.

Equally significant to his purely scientific efforts were Powell’s contributions to the creation of new scientific bureaus. His advocacy led directly to the establishment of the USGS and the Bureau of Ethnology in 1879. Powell was the second director of the USGS and he set the new agency’s path of providing critical scientific information to the public, while employing and supporting heralded geologists. USGS scientist Clarence Dutton’s glowingly descriptive prose indelibly imprinted the splendor of Grand Canyon on the American public, and GK Gilbert determined the evolution and structure of the Henry Mountains in a classic study. One of Powell’s greatest contributions was the initiation of a program of systematic topographic mapping of country. Under Powell, the USGS also began collecting hydrologic (stream) data. Both these efforts provided critical baseline data that greatly benefitted the growing country. Of Grand Canyon’s geology, Powell wrote, “the book is open and I can read as I run.”The landscape surrounding the Green and Colorado rivers still offers a window into the history of the planet. John Wesley Powell didn’t just put the Colorado River canyons on the map; 150 years later, all of us who live or travel in the American west follow his path in one way or another, whether it is by floating down the river, gazing at a canyon wall, or even merely using a topographic map app on our smart phone. Thanks to Powell, the canyon country is no longer the Great Unknown.

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

.jpg) This year marks the 150th anniversary of John Wesley Powell’s pioneering journey down the “Great Unknown;” e.g., through the canyons of the Green and Colorado rivers. Many events are ongoing this year in celebration of Powell’s epic journey, which was the last great exploration of the American west. One such commemoration is the Sesquicentennial Colorado River Exploring Expedition

This year marks the 150th anniversary of John Wesley Powell’s pioneering journey down the “Great Unknown;” e.g., through the canyons of the Green and Colorado rivers. Many events are ongoing this year in celebration of Powell’s epic journey, which was the last great exploration of the American west. One such commemoration is the Sesquicentennial Colorado River Exploring Expedition