|

| James Mauch |

New geologic research into the history of the landscape near Moab has yielded a much better understanding of how it has changed in the recent geologic past and how it continues to evolve. Geologists have long understood that the canyons, cliffs, pinnacles and other geologic features found near Moab are young, but until recently they have struggled to quantify the age of this landscape. The Masters of Science thesis completed in 2018 by Utah State University student James Mauch has significantly furthered our understanding of the origin and evolution of the canyon country surrounding Moab. One of the principle findings of James’ research was to constrain the age of Moab Valley and the surrounding red rock canyons at less than 1.5 million years old.

James and other geomorphologists (geologists who study how landscapes form) pay special attention to stream deposits because running water is one of the most important sculptors of landforms. Streams leave gravel deposits in floodplains when they are in equilibrium with the land and not actively downcutting. When geologists are able to determine when these deposits formed, they can obtain important time markers to constrain the age of a landscape. Unfortunately, stream deposits have been hard to date until recently when geologists developed techniques that measure either how long they have been buried, or conversely, exposed to cosmic radiation on the earth’s surface.

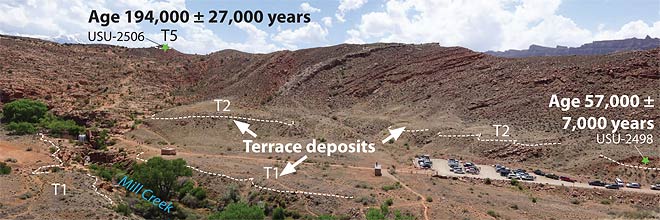

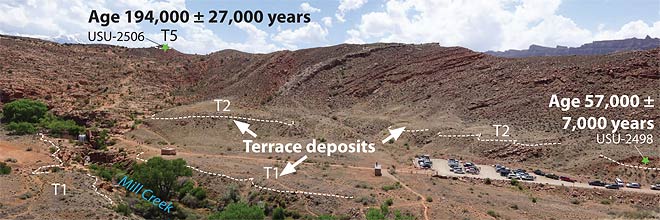

When a stream later erodes through its floodplain and into bedrock below, its gravel deposits can be left perched above the channel in terraces. When geologists date terrace deposits and measure their elevation above the current stream channel, they can calculate its incision rate, and can reconstruct the history of how the landscape has changed through time.

|

| James collecting a sample for analysis to determine when the terrace deposit was buried. |

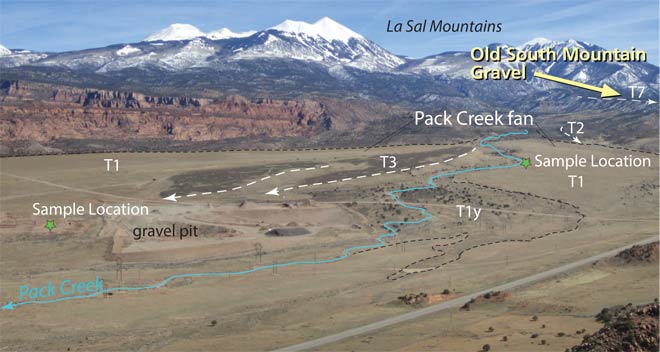

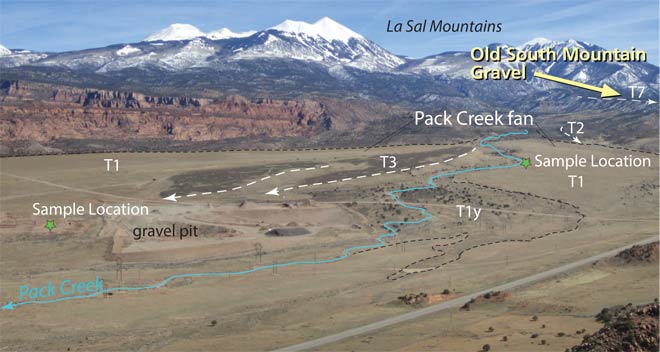

James used these modern dating techniques to determine when terrace deposits from Mill and Pack creeks formed, and the incision rates of these streams as they carved their canyons northeast of Moab-Spanish Valley. Moab-Spanish Valley was formed not by the action of rivers and streams (indeed, the Colorado River flows across it at nearly a right angle), but from the dissolution of underground salt in a salt anticline, which is a domed structure formed when salt deposits flow laterally and upward beneath overlying layers of rock.

James used the ages of the oldest gravel deposits from Mill and Pack creeks to constrain the overall age of the Moab and Spanish valleys. He examined gravels deposited on a ridge above Mill Creek southeast of Johnson’s Up-on-Top and on the flank of South Mountain, and determined that they were deposited prior to the formation of the Moab-Spanish Valley. These gravels formed 1.5 million years ago, indicating that Moab-Spanish Valley and the surrounding landscape are less than 1.5 million years old; e.g, very young geologically.

He also used some of the younger terrace deposits along Mill Creek to constrain how rapidly the Moab-Spanish Valley has been sinking due to salt dissolution over the last 200,000 years. In the center of the valley near the UMTRA site next to the Colorado River, the valley has dropped approximately 650 feet (200 meters) over that time interval, moving at a rate of approximately 0.04 inches (1 mm) per year, which is a surprisingly fast rate for such a geological process. Near the edges of the Moab Valley, the rate is approximately half as much; still a rapid rate of change.

During his research, James spent approximately 50 days doing fieldwork and geologic mapping in Moab and Spanish valleys, concentrating on the Kayenta Heights Fault Zone on the northeast side of the valley, and studying the stream profiles and gravel deposits in six different drainages near Moab. He said, “Mapping was when I really began to get a sense of how the landscape had changed through time. It also brought me to some stunningly beautiful and unexpected places. I’m still blown away with the quality of scenery in Moab and Spanish valleys.”

|

| Terrace deposits near the Mill Creek Trailhead, showing two sample locations and their ages. Note that the older terraces are higher above Mill Creek. |

|

| Oblique view of Pack Creek. T1 – T3 are young terrace deposits that have been tilted by the continued sinking of Spanish Valley. T7 is an older gravel deposit that James dated at approximately 1.73 million years old |

James developed his interest in studying geology while growing up on the western slope of Colorado. “From the scrubby bluff behind our house to the nearby red rock canyons, I was drawn to the sparse beauty of the high desert landscape.” Once he began his studies in geology, he found his personal exploration and academic studies were mutually amplifying. “The more I study the Colorado Plateau, the more I want to explore its backcountry, and the more time I spend in its backcountry the more fascinated I am by its geology and geomorphology.”

He continued, “It’s hard to emphasize enough to non-geologists what an amazing treasure-trove Moab is geologically. I like to convey with folks that the scenic resources and quality-of-life that residents and visitors to Moab enjoy are fundamentally linked to its geology. For scientists and nonscientists alike, it’s worth furthering our knowledge of geologic history, as, especially in Moab where the geology is so visible, it leads to an even deeper appreciation for the place.”

Many questions remain related to the origin of specific aspects of Moab’s canyon country and the overall timing of the erosion of the Colorado Plateau by the Colorado River, but James’ research has provided much new data and new insights that have increased geologists’ understanding of the geological happenings in and around Moab.

Special thanks to James Mauch, now a geologist with the Wyoming State Geological Survey, and his thesis advisor Professor Joel Pederson for their assistance with the preparation of this column. All images used with permission, courtesy of James Mauch.