| Geology HAPPENINGS February 2019 | ||||||||

The Long View: Deep Time in Moab |

||||||||

The concept of geologic time has been called the geosciences’ greatest contribution to human thought. This is a remarkable statement in light of what the science of geology has given us; ranging from everything from oil, gas, gold, and silver to concrete and clay. Further, the geosciences have fired our collective imaginations and enriched our intellectual lives with the discovery and description of prehistoric faunas such as the dinosaurs and trilobites, as well as by measuring that that the very continents that we inhabit are slowly moving relative to each other at the rates that fingernails grow. Geologic time, or “deep time” to use John McPhee’s memorable phrase from his classic book Basin and Range, is an essential component of every aspect of the science of geology, and has revolutionized our relationship with our planet.

Based on observations of the rock record and geologic processes, geologists concluded that the earth is very old long before the advent of the nuclear age, which enabled them to make a precise determination of that age in years. James Hutton, the 18th century scientist considered to be the “Father of Modern Geology,” concluded that geologic time was so vast, at least from our human perspective, that it had “no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.” Our planet is 4.5 billion years old—that’s 4,540,000,000 years old, if we write out all the zeros. The age of Earth can’t be determined directly from Earth rocks, since they are recycled through erosion and plate tectonics, but is measured from meteorites that share our planet’s origin. There are two main ways that geologists tell time, using a variety of techniques that range from common sense to nuclear physics. The first type of time-telling is relative dating, which involves determining the sequence of past geologic events. The second type, absolute age determinations, are numeric and identify the time in years when specific events happened, such as the deposition of a rock layer or the eruption of a volcano. We will cover absolute age determinations in future Geology Happenings columns, but here we introduce relative dating.

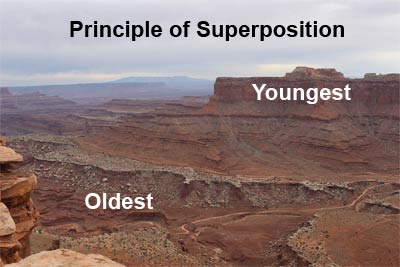

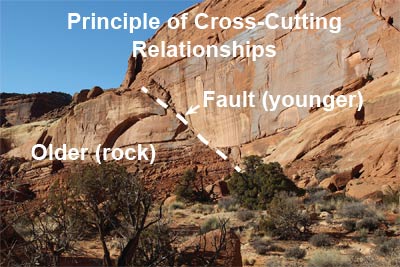

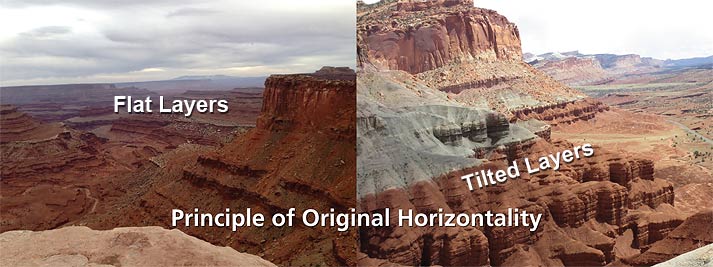

Geologists also use the Principle of Original Horizontality, which observes that sediments such as sand or mud are always deposited flat (i.e., in horizontal layers). The Principle of Cross-cutting Relationships further helps define relative ages because features that cut across one geologic layer must be younger than what is cut. To go back to our breakfast scenario, we can cut pancakes only after they are stacked. For example, the Moab Fault must be younger than the rocks cut by it.

We will learn more about how geologists tell time later, but for now let us consider just one simple fact held within southeastern Utah’s geologic history: sandstones found in rock layers near Moab were deposited in vast ancient sand dunes more than 150 million years ago when dinosaurs lived. Today we drive and mountain bike over rocks that contain these fossils and other features that tell ancient stories that are only accessible with a long view, and are of other times.

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

Geology forces those who practice the science to develop a long view. Even laypeople who just appreciate the geology of a region like Utah’s canyon country gain an appreciation of a time scale greater than our own. Geologic time spans intervals entirely different than our human one of days, weeks, months, and years. The events that make up the geologic history of Moab took place over intervals of tens of millions of years, occurring as long ago as hundreds of millions of years in the past. Developing a perspective on geologic time is one of the greatest intellectual challenges among all the sciences, right with understanding the vast distances found in interstellar space and the strange behaviors seen in particle physics.

Geology forces those who practice the science to develop a long view. Even laypeople who just appreciate the geology of a region like Utah’s canyon country gain an appreciation of a time scale greater than our own. Geologic time spans intervals entirely different than our human one of days, weeks, months, and years. The events that make up the geologic history of Moab took place over intervals of tens of millions of years, occurring as long ago as hundreds of millions of years in the past. Developing a perspective on geologic time is one of the greatest intellectual challenges among all the sciences, right with understanding the vast distances found in interstellar space and the strange behaviors seen in particle physics.