Springs and hanging gardens are oases within the redrock desert surrounding Moab. They are almost magical places where water emerges from rock, where delicate gardens of monkey flower, columbine and maidenhair fern grow, where visitors may hear the distinctive descending song of a canyon wren and escape from the searing heat of summer.

Springs and hanging gardens are oases within the redrock desert surrounding Moab. They are almost magical places where water emerges from rock, where delicate gardens of monkey flower, columbine and maidenhair fern grow, where visitors may hear the distinctive descending song of a canyon wren and escape from the searing heat of summer.

Water flows from rock only under the right geologic conditions. Springs are defined as places where groundwater flows onto the land’s surface or into a body of water, and also can be viewed as an intersection of the water table and the earth’s surface. While springs are extremely important biologically (especially so in dry environments), they are fundamentally geological phenomena.

Springs vary a great deal based on the underlying geology of an area, including types of rock present, the presence of faults or fractures in the rock, the characteristics of the underlying aquifer and the type of surface from which they flow; e.g., whether the water springs from a vertical cliff, a flat surface or into a stream or lake. In the American west, springs are classified into nine major types, including geysers, springs that flow into stream channels (rheocrene), springs that flow into wetlands (helocrene), and hanging gardens. Hanging gardens are not very common in most areas of the west except for the Colorado Plateau and the canyon country of southeastern Utah and northern Arizona, where they are a characteristic part of the landscape.

Springs vary a great deal based on the underlying geology of an area, including types of rock present, the presence of faults or fractures in the rock, the characteristics of the underlying aquifer and the type of surface from which they flow; e.g., whether the water springs from a vertical cliff, a flat surface or into a stream or lake. In the American west, springs are classified into nine major types, including geysers, springs that flow into stream channels (rheocrene), springs that flow into wetlands (helocrene), and hanging gardens. Hanging gardens are not very common in most areas of the west except for the Colorado Plateau and the canyon country of southeastern Utah and northern Arizona, where they are a characteristic part of the landscape.

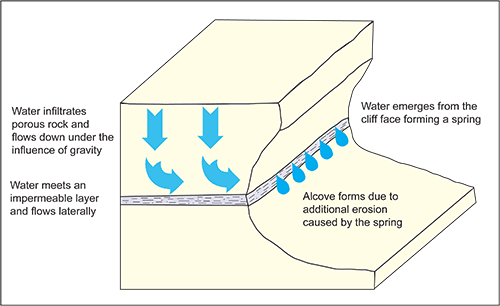

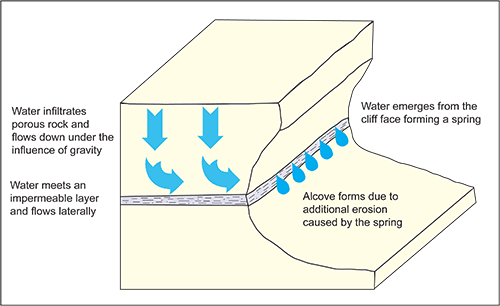

The sandstone layers around Moab, such as the Navajo and Entrada, are geologically a bit like a sponge. Groundwater is able to fill the ample pore spaces between round grains of sand in the rock. Following the pull of gravity, water flows downhill through permeable sandstone layers. When it hits a less permeable layer, which sometimes may consist of just a small lens of a more clay-rich sediment within a rock layer, or at the contact or boundary between two layers, it begins to flow laterally, since further progress downhill is blocked. When this groundwater reaches the face of a cliff, it emerges as a spring.

The sandstone layers around Moab, such as the Navajo and Entrada, are geologically a bit like a sponge. Groundwater is able to fill the ample pore spaces between round grains of sand in the rock. Following the pull of gravity, water flows downhill through permeable sandstone layers. When it hits a less permeable layer, which sometimes may consist of just a small lens of a more clay-rich sediment within a rock layer, or at the contact or boundary between two layers, it begins to flow laterally, since further progress downhill is blocked. When this groundwater reaches the face of a cliff, it emerges as a spring.

Hanging gardens are, as their names imply, springs or seeps that emerge from the surface of cliff faces and are adorned with vegetation growing on vertical or overhanging surfaces. The term “hanging garden” may be taken from the famous hanging gardens of Babylon, or may merely be a simple description of the verdant vegetation growing along these spring orifices.

Sometimes hanging gardens are supported by mere seeps, where the flow of water onto the surface is so minimal that it doesn’t do more than dampen it. In other places, water can be seen actively dripping from the rock face or in a small pool

|

| Cave Primrose (Primula specuicola) |

.

Many hanging gardens are found in large alcoves that are eroded into cliff faces by the water as it emerges. The presence of any additional water, even from the smallest seep, enhances weathering and erosional processes, with alcoves growing deeper progressively through time. These alcove hanging gardens are distinctly cooler than the surrounding area, and depending on slope aspect and size of the alcove, may receive little direct sunlight.

The hanging gardens in the Moab area have distinctive vascular plant assemblages and a variety of mosses, fungi and other microorganisms. White staining on cliff faces where springs and seeps emerge is essentially hard water deposits of calcium carbonate and other minerals that precipitate at the surface as water is evaporated. Black staining is a combination of mineral deposits and “biofilm.”

While only making up a tiny portion of the overall area of the Colorado Plateau, hanging gardens and other springs are some of the most biologically diverse areas of canyon country and may be home to a variety of invertebrates, amphibians and mammals and to unique suites of vegetation. Endemic plant species (those that are native to a restricted area) are especially characteristic of hanging gardens in southeastern Utah. Five percent of the vascular plant species found in Colorado Plateau hanging gardens are endemic to the region. The cave primrose (Primula specuicola) is one such endemic species. It was first collected in a hanging garden near Bluff in 1895. This beauty grows only in moist areas at seeps and in hanging gardens on the Colorado Plateau. As one of the earliest blooming plants in canyon county each spring, it is also known as Easter flower.

Springs and hanging gardens may be seen near Moab in Grandstaff and Hunter canyons, in addition to numerous inaccessible hanging gardens present on vertical cliffs. In Canyonlands National Park, the Neck Springs Trail loops past several hanging gardens in large alcoves that were used as water sources by cowboys prior to park establishment. The presence of water and lush vegetation make Grandstaff and Hunter canyons especially popular hiking trails, but the springs that support these canyon ecosystems are fragile. Foot traffic can cause erosion and trample native plants. Hanging gardens are also threatened by invasions of nonnative plants that displace natives.

Springs in the desert are places where the truth behind the phrase “water is life” is especially evident. Knowing the basics of the geology of springs expands this concept. Since springs form only where the geology allows them to be, geology becomes the bedrock (pun intended) of life, at least in the hanging gardens growing in the canyons and alcoves around Moab.

You can read more geology articles from Allyson HERE

A self-described “rock nerd,” Allyson Mathis is a geologist, informal geoscience educator and science writer living in Moab.

A flat-lander by birth from where everything was covered with vegetation, Allyson is much happier exploring deep time in Moab and beyond. |

|

Springs and hanging gardens are oases within the redrock desert surrounding Moab. They are almost magical places where water emerges from rock, where delicate gardens of monkey flower, columbine and maidenhair fern grow, where visitors may hear the distinctive descending song of a canyon wren and escape from the searing heat of summer.

Springs and hanging gardens are oases within the redrock desert surrounding Moab. They are almost magical places where water emerges from rock, where delicate gardens of monkey flower, columbine and maidenhair fern grow, where visitors may hear the distinctive descending song of a canyon wren and escape from the searing heat of summer. Springs vary a great deal based on the underlying geology of an area, including types of rock present, the presence of faults or fractures in the rock, the characteristics of the underlying aquifer and the type of surface from which they flow; e.g., whether the water springs from a vertical cliff, a flat surface or into a stream or lake. In the American west, springs are classified into nine major types, including geysers, springs that flow into stream channels (rheocrene), springs that flow into wetlands (helocrene), and hanging gardens. Hanging gardens are not very common in most areas of the west except for the Colorado Plateau and the canyon country of southeastern Utah and northern Arizona, where they are a characteristic part of the landscape.

Springs vary a great deal based on the underlying geology of an area, including types of rock present, the presence of faults or fractures in the rock, the characteristics of the underlying aquifer and the type of surface from which they flow; e.g., whether the water springs from a vertical cliff, a flat surface or into a stream or lake. In the American west, springs are classified into nine major types, including geysers, springs that flow into stream channels (rheocrene), springs that flow into wetlands (helocrene), and hanging gardens. Hanging gardens are not very common in most areas of the west except for the Colorado Plateau and the canyon country of southeastern Utah and northern Arizona, where they are a characteristic part of the landscape. The sandstone layers around Moab, such as the Navajo and Entrada, are geologically a bit like a sponge. Groundwater is able to fill the ample pore spaces between round grains of sand in the rock. Following the pull of gravity, water flows downhill through permeable sandstone layers. When it hits a less permeable layer, which sometimes may consist of just a small lens of a more clay-rich sediment within a rock layer, or at the contact or boundary between two layers, it begins to flow laterally, since further progress downhill is blocked. When this groundwater reaches the face of a cliff, it emerges as a spring.

The sandstone layers around Moab, such as the Navajo and Entrada, are geologically a bit like a sponge. Groundwater is able to fill the ample pore spaces between round grains of sand in the rock. Following the pull of gravity, water flows downhill through permeable sandstone layers. When it hits a less permeable layer, which sometimes may consist of just a small lens of a more clay-rich sediment within a rock layer, or at the contact or boundary between two layers, it begins to flow laterally, since further progress downhill is blocked. When this groundwater reaches the face of a cliff, it emerges as a spring.